Medicine, we have shown, is not a mystery based on knowledge that can be the property of only a few, but a method of restoring and maintaining health that can be learned by all who have the time and opportunity to study it and of which the doctors are the accepted custodians and translators. The human body being a complicated mechanism and the diseases to which it is heir many, the ways in which doctors must assist it in its fight have become so varied, and involve so many branches of special knowledge, that, as we have seen, it is never possible for a single doctor to possess and be able to use all the knowledge and skill medical men have acquired, for so many kinds of doctors and so many forms of service are needed in the modern civilised world.

In no country has the development of Medicine been a conscious and planned procedure; new knowledge has been grafted on to old and ancient methods and anachronistic procedures have remained side by side with scientific advances which have been as rapid in this field as in any other. Hospital buildings, designed to last a hundred and more years, have tended to influence the retention of a system of staff appointments arid methods of working that have vanished from every other profession. Charity has become inextricably mixed with systems of collecting money from even the poorest, and doctors have surrounded themselves with an ethical code which prevents them dealing as they should with the evils of both orthodox and unorthodox methods of healing.

This ethical code has developed because the profession has felt that Medicine should not be governed by the ordinary rules of business and that so necessary is the work of the physician to mankind as a whole that his service should not be bound by financial considerations. The young doctor is therefore supposed to dedicate himself to humanity and to dare all and do all in that service. Yet he soon finds himself up against the type of economic and social difficulty which we have discussed. The ethical code has long lost its altruistic nature and in a large measure consists of regulations for enforcing what might be called fair business practice. The ethical guardians of the profession can do little more, as Sigerist says, than try to avoid “the worst abuses of competitive business ,by forbidding advertising, splitting of fees, taking patients away from a colleague, making money from patients, avoiding competition through contract practice, etc.” It is only when Medicine ceases to be a trade or business and doctors can regard their patients without any consideration of fees, either their own or those of specialists or charges in hospitals, that these modern additions to the basic altruistic code of Medicine become clearly superfluous and without meaning, When all questions of fees have been banished the perfect relationship between patient and doctor can be established. There can then be only one standard of medical attention, only one class of patient, and the whole of medical science can be used for his benefit. It is for this reason that many now believe that a medical service based on the maintenance and restoration of the health of every individual must be financed nationally and made freely available to all. Since Medicine involves so many specialists, so much intricate and costly machinery, since it needs the co-operation of so many different professions and the correlation of disease prevention with the greater national questions of environment and nutrition, it cannot be effective unless it is available completely to all. Its basis then becomes scientific, and as disease loses its “magical implications” it can be considered —as it is in fact— a biological process that has, to be faced openly and to be treated scientifically. The extent to which that occurs may, of course, depend on the clarification of the ethical and rational foundations of the whole State, but there is no reason why Medicine should not reach that stage even in advance of other professions.

This development cannot, however, take place while, as Sigerist puts it, “the fight against disease is not led by one general staff but by a multitude 6f staffs among which there is often little or no co-operation.” It is clear that a complete medical service available to every citizen at all ages and all times must be led and controlled by a central organisation, a Ministry of Health. That we have such a body is due, not as it should be to the recognition of past Governments that a health service is needed, but to the accumulation of those unprofitable cases of which we have spoken and of the need for the State to step in and handle them since no existing medical organisation could or would do so.

The Ministry of Health must, therefore, be not only reorganised but given a completely new orientation to the question of health. It must be the inspiration and guiding force of the new medical service ; it must visualise disease prevention as no British Minister of Health has ever had the chance to do; it must lay down the principles on which the service is to stand; it must see that the equipment, machinery, buildings, and personnel are available wherever needed. It will have to move far beyond its present narrow orbit and become the mainspring of all movements to improve the environmental conditions of the country.

A service controlled by the Ministry of Health must obviously be a national one, and the term brings to mind all those bogies of bureaucracy and red tape which have in the past led doctors to fear the intervention of the State in medical matters. We shall make it clear that in matters affecting the individual patient no one has any right, or will be given the right, to interfere between the doctor and his patient except his own colleagues and those of higher standing in the profession. The “Whitehall bureaucrat” has no part in a modern medical service beyond those indicated—relating it to other services and guaranteeing that a minimum service will reach every person in the country.

That a State medical service can be so constructed as to avoid the evils of “muddling bureaucrats” appears impossible to many of the older members of the medical profession who are far from moderate in their criticism of our civil servants, of whom, in this connection, the late Sir Henry Brackenbury, of the B.M.A., recently wrote : ” The qualities required of the Civil Service are in many respects the antithesis of those needed in the actual practice of Medicine.” He went on to say, “The indifferent physician may well find his best interests served by a bureaucratic system with office hours and a pension,” This attitude is as unfair as that which classifies, all doctors as ” money-grabbers,” or stigmatises the panel practitioner as interested only in the financial side of that system because some doctors make the double standard of treatment to which patients are liable too obvious

The same critics are also fond of dogmatising about the evil effects of security upon men, and declare, as did a writer in the British Medical Journal recently, that “a fixed salary destroys initiative and ambition.” This slight to a very large proportion of men and women was very ably answered by a well-known Medical Officer of Health who, speaking as a “‘fixed salary man,” asked if this attitude was to be applied to all who, enjoy financial security. ” These include the Archbishop of Canterbury and all his bishops ; the Prime Minister and every member of the Cabinet; every admiral in the Navy, every general in the Army, every marshal in the R.A.F., and all their officers and men ; the headmasters and staff of the public private, and State-aided schools ; the Civil Service; the judges; and all staffs of municipalities. It does not include such varied ranks of society as professional men in private practice, small shopkeepers, hawkers, millionaire motor magnates, and a number of the clergy.”

It is clearly false to suggest that a man only does work that he is paid for doing and in which he is vitally interested when he is going to get in return something more than other men get. In the case of doctors there is no evidence that those in salaried positions do less than those in private practice, for all doctors are fortunate in doing work which is ever varied and ever valuable, providing incentives greater than any financial motive.

These opponents of a rational medical system forget that: for many years an increasing number of doctors have been employed by State and local authorities in salaried services, that the whole of the medical services of our fighting forces and a considerable number of all hospital doctors, especially laboratory specialists and research workers, are enrolled in services correlated as is the Civil Service. None of these doctors has found it impossible or even difficult to give his best service to the sick, and their experience has made it clear that a medical service is an ideal ground for the testing of new democratic ways of providing for the needs of the population; the nature of the relationship between doctor and patient is; such that the doctor can always make it clear that his responsibility for the life of his patient allows no interference by lay people however important.

We do not claim that this lesson has been learned everywhere in our existing organised medical services. In the change-over from the Poor Law to the municipal hospital the hospital committees have often remained under the control of chairmen who possessed an attitude towards the patients which was reminiscent of that taken towards the “indigent poor” about fifty or sixty years ago. That the Poor Law hospital had advanced at all before the passing of the Local Government Act was in large measure due to the influence of medical officers who forced concessions from such lay controllers by insisting that they must be the sole judges of what was required and what was to be done in questions affecting , the health of the patient.

The medical service of the future, however, will not depend on the isolated action of far-seeing doctors but will be so constructed as to contain within itself the safeguards that are necessary for the separation of medical attention from lay control and even, in some instances, from official control by medical administrators. This will necessitate, in addition to the Ministry of Health, two further administrative stages — one related to the universally accepted view that in Medicine (as in most other activities, defence, transport, electricity, and water supply) the controlling authority of the future must cover a wider area than any existing local authority, for we must free ourselves from centuries-old boundaries which bear no relation to the changes wrought by the growth of industry; the other intensely democratic, responsive to the needs and wishes of every individual citizen, and directly concerned with the medical service of its own neighbourhood.

The first of these forms of organisation is generally spoken of as “regionalisation” and is accepted by all medical organisations as one of the lines of future development. It is the basis of the work of the Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust and has been accepted by the Ministry of Health as one of the steps to be taken in post-war reconstruction. Mr. Ernest Brown, as Minister of Health, has stated that “the task of converting theories of regionalisation into concrete and workable proposals is one which calls for the application of much careful thinking.” There is still, however, much talking about regionalisation which is far from clear, and the term has not yet received a generally accepted definition.

So far as the, administration of the medical services is concerned, regionalisation would necessitate the establishment of the Regional Medical Service Committee. This involves dividing the country into a number of Regions which will get rid of those local government boundaries which pay no regard to natural social and economic groupings and so inevitably create problems. This is not a question of increasing the area or population to be controlled: by the new regional authority, for it is conceivable that investigation would show that in this or that area the necessary co-ordination could only be obtained by changes which would lead to a diminution of the population falling within a particular region. In general, however, it would lead to a wider region than any now in existence, and this should bring about greater efficiency and economy, for all organisations which have studied the question believe that a great deal of readjustment and co-ordination, can be effected without additional expense. At the same time a great improvement in the internal arrangements and organisation of local authorities must be made and the present multiplication of public and voluntary bodies concerned with health greatly cut down.

The method of election of these Regional Authorities must be settled for the whole country and for all public services, as most of the latter will also benefit from this form of control — one which will lead to carefully thought-out plans for wide areas instead of improvisations in many small districts. It will be the work of these committees to consider the national plan as prepared by the Ministry of Health and to relate the service to the needs of every citizen and group in their areas. It will be for them to see that the service does, in fact, exist in a form that makes it accessible to all; it will be for the doctors in the smaller units to inspire the system with the spirit of service which will make it a living thing.

Among the problems which the Regional Medical Service Committee will consider is the number and distribution of hospitals in its area. There will, of course, be active cooperation between the areas so that overlapping is avoided at the new boundaries, but the latter should be fixed so that, in fact, overlapping is almost impossible. The whole question of hospitals bristles with debatable points which we have not space to discuss ; and since it involves the co-operation of architects and town-planning experts it cannot be finally settled until the principles of town-planning have been agreed upon. If, as medical men would suggest, our towns are restricted in size, if houses are planned in relation to industry: and transport, if they give maximum light and air and look out on growing trees and grass, there will be no difficulty in placing hospitals in suitable sites within the town. Our conception is that all hospitals should be placed in the closest proximity to the patients who will use them and to the domiciliary doctors whom they will serve and who will form part of their staff. But so long as we are faced with unwieldy unplanned cities such as London we may have tomodify that We may perhaps want to, put some hospitals in the open country; that should not be necessary provided convalescing facilities are adequate, but it emphasises the need for relating our hospital provision to other developments,

Hospitals have in the past been built as too-permanent structures. While it is true that the presence of Harley Street consultants on the staff of London hospitals and the need for them to be so situated that they can fit their “charity ” work’ into the framework of their private practices has had a certain influence in keeping some of the London teaching hospitals at sites no longer advantageous and in buildings quite un-suited for modern work, the value of the buildings themselves and the permanence of their walls has been the chief factor. Those who, had to proclaim to the charitably minded “The hospital is falling down” so as to collect money for needed improvements would have been more truthful from a medical point of view if they had proclaimed that the needs of patients and doctors demanded new and different buildings.

Whether we can devise new methods of hospital building which, will enable us to embody all scientific departments and yet be elastic enough to meet those new demands which are today as little guessed as were our needs in the era before operating theatres and laboratories is a problem which has not yet even attracted attention. Whether we should build upwards for light and air and convenience of transport or outwards-—as at present— getting light and air at the expense of long corridors, time-consuming distances, and expensive heating and lighting systems is one of the questions yet to be debated. Another is how we can serve invalid food on a large and economic scale. Such questions as these will be dealt with by the Regional authority, which will also see that the funds available are evenly distributed.

But it is only when we come down to the smaller administrative unit, which we may call the Local Health Unit, that the form of our medical service as it affects the individual citizen and the individual doctor becomes clear. Once more it is worth recalling that forms of State medical service and national medical service— terms so often used by those intent on preserving the present system— canbe constructed in a fascist State or in a democratic state controlled by laissez-fairemethods. A medical service which will get rid of the chaos, the difficulties, the overlappings, the inefficiencies, and extravagances of the, system of pre-1940 must be based on totally different conceptions and methods.

Progressive doctors have in recent years agreed that the basis must be the Local Health Unit, which as its name implies should be a unit of a size and form dictated by local conditions and constituted for the purpose of preserving health. In each of the large regions already visualised there will be as many local units as the population requires, and each unit will, with certain highly specialised exceptions, provide a complete service for the preservation of health and the treatment of disease. From what has been said in earlier chapters it will be seen that it must be based on the provision of a general, practitioner doctor for every individual, that that doctor must be a member of a group of doctors providing all specialists, and that the service must be centred on a large hospital at which provision has been; made for all the medical needs of the community.

We must therefore have a clear idea of the size of the unit and in some respects this depends on the hospital, and constitutes indeed one of the problems which the regional authority will have to debate. Hospitals vary in size from the tiny cottage hospital of some 20 beds or less to huge mental hospitals of 2000 beds. General hospitals with full medical and surgical facilities vary from some 300 to 1500 beds; in some, out-patients form the greater part of the work done.

Below a certain size no hospital could find employment for a full staff above it administration becomes difficult, duplication of departments may be necessary, and it is almost impossible to maintain that spirit among the staff which leads to harmony and real team-work. When, as we propose, the general practitioners of the unit are amalgamated with the hospital staff, too large a unit would lead to the same type of difficulty which exists today.

To put it dogmatically, all considerations point to a hospital of 1000 to 1200 beds as being the largest likely to be suitable, and the lower figure may prove adequate for the given unit of population, namely, 100,000 people. Our best-served cities still have fewer than 10 beds per 1000 potential patients, the figure here taken, but as some reach over 9, and there is evidence that that is not quite adequate, some consider a hospital of the higher number of beds, 1200, would be needed. We anticipate, however, much more work being done by general practitioners in consultation with specialists and a steady improvement in the health of the population, so that we are probably safe-in visualising our Local Health Unit hospital as having 1000 beds for all purposes.

The hospital of the Local Health Unit would sweep away the invidious selection system of the large voluntary teaching hospitals and the remnants of the administrative methods and defects of the Poor Law still inherent in the municipal hospitals. There would be an open door not only to the cases of interest from a technical point of view, the “interesting and stimulating” surgical-cases, and those admitted because the consultant wishes to propitiate his clients, the general practitioners, but to those equally ill but less interesting and chronic patients who are now diverted to the municipal and Poor Law hospitals. Both patients and doctors would benefit from the wider variety and hospital finance and administration would be less difficult.

In a hospital of this size enough beds for all types of cases can be provided. While their allocation and that of the staff are technical matters in which doctors are vitally interested, it may be; stated generally that for such a unit some 50 doctors would be needed for the hospital and probably 33 for the domiciliary service, making a unit staff of 83.

It will at once be clear that this is an almost ideal unit for the type of service we have discussed, responsive to the needs of the patients, easily controlled, easily infused with a spirit of social responsibility, and small enough for every man :and woman on the staff to be aware of the standard expected and of the class; of work put into their departments by every colleague. In such a unit it would be impossible for that fear of the “maintainers of tradition “—red tape; slack and unprofessional work— ever to raise its head. The contact of colleagues, the sense of one’s importance to the community, and the awareness of how much one’s efficiency means to that community would raise every doctor to a standard of proficiency attained only by the best to-day.

The greatest change we have to suggest in the hospital is in the out-patient department. Of the three main functions of these departments at present, it is generally agreed that two should not be performed by hospitals at all as they can be provided better in other ways. “Casualty” work, which should be confined, but rarely is, to dealing with slight and sudden injuries, and the giving of advice to those who come direct to the hospital for diagnosis and treatment are functions which, in fact, should be carried out by the general practitioner and would be but for economic difficulties and lack of equipment and facilities. The doctor’s consulting-room is no place for minor surgery, and in any case the doctor is too seldom available just when the casualty occurs. The third function of the out-patient departments, and in the opinion of many the only true function, is to provide a service of consultants to whom other doctors can send cases.

Even this, however, is not closely related to the purpose of the hospital, which is to admit patients for forms of treatment only possible inside the hospital. In fact, all these functions can be provided for at a Health Centre, and this conception marks the difference between the Medicine of the past and the health service of the future more than anything we have discussed. An adequate description would need many chapters and much must be left to the imagination of the reader who, if he has followed our arguments, should be able to fill in the details.

The Health Centre we wish to describe has no existence in this country, although the Pioneer Health Centre at Peckham is in many ways an inspiration. At such a Centre would, be focussed all the health activities of the Local Health Unit. Built close to or as part of the hospital, it would co-ordinate the work of the domiciliary doctors, it would act as report and record centre for the unit, it would make consultation between doctors and the provision of specialist services exceedingly simple, and it would become the place to which at all ages the population would turn for advice and help in maintaining health and fighting disease. It would supersede the individual surgeries of the 30 or so doctors on its staff, but so that no difficulty would be placed in the way of patients, subsidiary clinics, related only to the domiciliary service would where necessary be established among the most densely populated areas.

The Health Centre would be the place at which the home doctors would see those cases not requiring to be visited and from which they would set put on their home calls. The adequate secretariat would deal with all requests for visits, and complete, up-to-date records of the health and illnesses of every patient would, be kept.

How important this keeping of records is will be recognised by anyone who has been ill and who has tried to answer the doctor’s questions about previous illnesses. It is an essential part of diagnosis to take a careful history of the patient and many medical men have fallen into errors by neglecting routine inquiries about the health of the patient and his family. Apart from those familiar, hereditary and congenital diseases in which the history is of obvious importance there are many conditions in which a knowledge of previous illnesses will immediately clear up the position. As an example, one may contrast the making of a diagnosis of a tropical disease in a patient who has never left England with the failure to recognise a tropical disease through lack of knowledge of recent visits by the patient to countries in which the condition is common.

All doctors agree that knowledge of the patient’s history is important. Those who desire to perpetuate the present lack of planned Medicine claim that the ordinary family doctor acquires a full knowledge of his patients and so can judge each illness in the light of previous ill health. This, is false unless one visualises a small community in which neither patients nor doctors change much over a long period of years, and even then any break in the continuity would mean the complete loss of all knowledge of the patient’s previous health standard.

True continuity is possible only when a complete record of the normal health of the individual, his general development and nourishment, his blood condition, and his freedom from detectable defects, can be placed alongside the history of any new disease, arid the results of examinations and tests compared. With the best will in the world no ordinary doctor can under present conditions, keep full notes of every patient and few patients who change their district and their doctor are able to convey anything like a complete picture of their own health standard. Doctors working at a Health Centre would not only have adequate time for full investigations of al complaints but every person would be encouraged to attend for periodic examinations, so that a continuous record of every citizen would gradually be built up and would be available wherever the patient attended for medical advice. How much, time would be saved in this way it is impossible to calculate, but years of hospital experience and contact with large numbers of general practitioners suggest that it would save many hours in every doctor’s time and much re-duplication of laboratory and; other tests. To a patient, to give a very common, example, the taking of any sample of blood is a blood test and the result a hidden mystery; to the doctor an accurate record of all blood tests taken and of the results might be of inestimable value.

The keeping of such records necessitates the employment of large staffs specially trained for this work. It has been objected that the examination and inquiries of a doctor are secret and confidential and that the intervention of lay staff would be a breach of professional etiquette. This, like so many other arguments, is but an apology for those doctors who are incapable of keeping an accurate record or cannot afford a secretary; in Harley Street it is an essential that a consultant should employ a secretary who makes and keeps the fullest possible notes. This atmosphere of the confessional which some of our more primitive medicine men would like to see preserved is a relic of the days when disease was regarded as a punishment for sin, when the spite of God or the machinations of the Devil seemed the only possible explanations for sudden illness caused, as we now know, by invisible germs.

The Health Centre would not only provide the base for the domiciliary service but would combine the functions of the doctor’s surgery and the hospital out-patient department. Those who pretend to understand what is suggested for the medical service of tomorrow always sneer at “clinic” medicine. They fail to see how helpful the Health Centre would be both to the sick and to the doctor. The doctor seeing a case at the Health Centre would have at his service in the same building or in the related hospital every specialist whose assistance he might want. Instead of cudgelling his brains as to where he could send Mrs. Smith for a second opinion, a blood-count, or an X-ray with a view to admission to hospital, he would only have to step across the corridor to an esteemed colleague who would arrange the necessary tests and give his opinion without interminable delay, and without Mrs. Smith having to come up over and over; again and sit in that draughty waiting-hall. If she did have to come back again she would come at a time when she would know she would be seen to the minute, and if she had to wait for hours while the tests were being done she would find comfortable and soothing surroundings in which to wait. If she had to bring the baby she would find the creche, in the same building, an excellent place to leave him for a few hours. And if she had to go into hospital it would be arranged there and-then without any: difficulty about a bed and without any, heart-burnings about the cost; she could leave the baby in the day nursery; and her own doctor would only have to go up in the lift after his morning surgery to see how she was progressing.

The Health Centre would be a busy place. It would have one great advantage not yet mentioned. To it would come every citizen while well and so they would become familiar with the place and its wonders while free from the worry of ill health. They would learns for the health education and health .preservation activities of the community would be centred there, to turn to the Health Centre whenever they felt; the slightest thing wrong. The presence of the healthy undergoing the same type of test and examination as the sick in the same building and by the same doctors would alter the whole attitude of the community towards disease and give the doctors a balanced view of the normal and the abnormal at present impossible.

The doctors, too, would look to the Health Centre as the hub of all their activities. Here their hours of leisure would be arranged and guaranteed; here they would do their turn of night duty ; here they would see in operation that new conception of Medicine, a complete chain of medical services always available to all, but a chain in which no link was overstrained. Here they would find colleagues able to advise, criticise, and correct, and here they would gain that wider knowledge and experience which is the never-ending search of every doctor throughout his career.

Part of the staff of the Health Centre would be home visitors who would help the doctor to build up a picture of the social background to every case he saw. To them would fall the duty of seeing that the home of the sick person— breadwinner or wife—did not deteriorate while they were in hospital. Through them would be provided that home help which would ease so much of the struggle to avoid prolonged illness which leads so many to delay treatment until it is too late. This home help, though, would not in a fully integrated medical service be so urgent, as at present for there would be adequate provision of day nurseries and nursery schools so .that care would always be taken of small children.

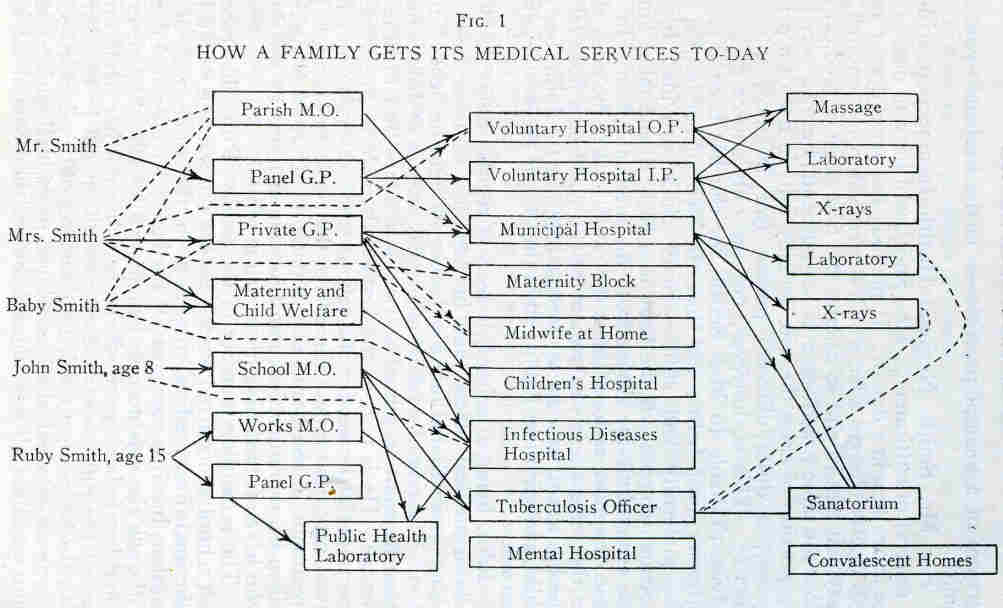

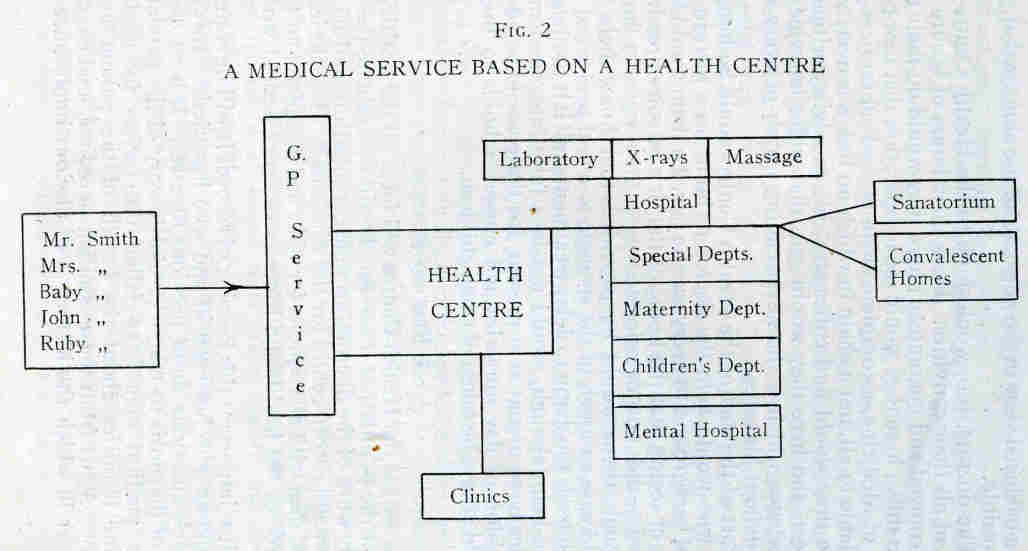

We are now in a position to describe the structure of this proposed medical service and to contrast it; with the present position

The medical life of the community is based on the Health Centre. For the Smith family there is only one route to a complete medical service, through the general practitioner service of the Health Centre, but by that route all specialist and consultant services are available in the home and at the Centre. Admission to hospital is also through the Centre and from both Centre and hospital there is certain access to convalescent homes arranged on modern lines. There is no re-duplication of services; the same laboratory, for example, serves the community at all stages.

The Smith family now know exactly where to turn for every medical need and have no fear of accepting the offer of specialist help, for they have, as taxpayers already paid for the whole service. The whole Smith family would now obtain every medical ‘service at the Health Centre. To begin With they would turn to the Health Centre for advice on all matters of health preservation, and this advice they would get individually or as part of the community, health exhibitions, film shows, and talks being a constant feature of the Centre. They would also attend for periodic examinations in the course of which early disease changes might be found long before they were severe enough to produce symptoms. In the case of illness the general practitioner would be seen at or summoned from the Health Centre. He would set, in motion the machinery for diagnosis treatment, and convalescence. Those services which Mrs. Smith and the baby already enjoy at a clinic would still be available, and any service Mr.; Smith, and the younger members of the family as they leave the school, need in connection with their industrial employment would be obtainable at or in relation to the Health Centre.

The implications of such a service will have become apparent to the reader. In the first instance all doctors employed in the service must be full-time salaried officers, with all the advantages that implies. Given an education in the social, background of disease they will be able to apply themselves vigorously to the prevention as well as the cure of disease, and to apply themselves without ever haying to consider the financial position of their patients. The total cost of the service will be such that the State will accept the burden as its own and the service will be freely available to the whole community. This will not prevent any who are so possessed of anachronistic anti-social habits as to wish to make their own arrangements to “contract out” of the service if they can find a doctor to attend them ; nor will it prevent a doctor, from setting up in practice if, without any of the advantages the rest of the profession would enjoy at the Health Centre and hospital, he thought he could attract enough patients to earn a living. As we already indicated, the number of people who might refuse the service thus provided would be very small indeed.

The service would also be available at all times. This appears to some to be a revolutionary conception which would undermine the morale of the people in a way that not even Hitler with all his air raids has done, for it is thought to be an inherent instinct of the British people to make abnormal demands on anything they know is free and available at all times. That this is a habit of any race is probably quite untrue, but there is evidence from many places that in the case the medical service it is quite without foundation. The greatest fear of the doctor is that he should be called out unnecessarily and especially at night. On the former point the experience of, for example, the Glasgow Outdoor Medical Service is that when people know they can always see the doctor at the Health Centre the number of urgent visits drops at once and in any case no doctor working at a properly organised centre is ever likely to be over-worked or to take anything but a pride in the number of calls made on him during his rota of duty, At the moment not only is the individual doctor often brought out unnecessarily but the medical profession as a whole has calls made upon it which no other profession or trade would tolerate. It is every doctor’s fate to return from a round of visits to find new calls waiting for him in the streets he has just left; and, more wasteful still, for a number of doctors to be visiting in the same street at the same time.

Dr. S. F. Marwood, writing in the British Medical Journal, has discussed this point in relation to so-called “free choice” of doctor. “It would seem,” he says, ” that, with the advent of a State service, freedom of choice must be limited to consultations at appropriate centres at appropriate hours, and that, unless the present uneconomic system is perpetuated whereby several doctors are visiting the same small district or even the same street on any one day, it must be dispensed with in patients homes.”

The answer to the second point —unnecessary night calls —is twofold. As with day visits the greatest cause of calls on the doctor after dark is the economic difficulty of the patient who bears pain, temperature and other disability moderately well during the day but is apt to be panic-stricken when darkness falls or when the temperature rises in the evening. This outweighs the cost involved and the doctor is hurriedly sent for, particularly when the patient is a child ; and every doctor can tell of being called at midnight to see one with a sore throat whose parents, well aware of the times sore-throats have cleared up without medical intervention, have not suspected diphtheria until the child got worse in the evening, and: have felt that whatever the cost they, must get advice. Remove this economic barrier and doctors will only be called out at night by the real emergency.

The second point is that while the service will be continuously available the individual doctor will not be, as at present, continuously on call. Doctors who have so often told men to rest and avoid over-work are almost the only workers who are expected to be on call for the whole twenty-four hours. In the Local Health Unit night work will be done on a rota system and each general practitioner will be on duty at intervals which, according to the needs of the system and the presence or absence of particular epidemics, may be as infrequent as one week in every ten. It is true that he may occasionally miss seeing an emergency in a family in which he feels a special interest, but he will not be— as he would today were another doctor called in his absence— unaware of it, for the health record of the patient will be available to him, and if he likes he can see the case in hospital or discuss it with the colleague who happened to be on duty.

We have spoken of the need for working out the basis of election of the new Regional organisations of the post-war Britain and in particular of the Regional Medical Service Committee. How is !the Local Health Unit to be organised arid controlled? It is clear that the Regional form of organisation, while it will have great advantages in improving services, will not be so “democratic” in the sense of direct election as some of our present authorities. Its functions should however, not be adversely affected thereby. The Local Health Unit, however, must be responsive to the needs of every member of the community it serves, and must therefore be controlled by a committee unlike any existing body. Its duties should be simple if the unit possesses that spirit which unity for health gives to a community, but it must be alive to its own problems and must represent the three groups who are interested in this affair of preserving health, the well, the sick, and the professional groups charged with the work involved.

This problem can only be solved in the light of the decisions the medical profession make as to the extent to which they desire to assume control Some have suggested that the medical superintendent of the hospital shall be the chief administrative: officer responsible only to the Unit committee. (The Medical Officer Of Health as we know him today will have functions outside our present consideration, dealing with community problems such as those of Sanitation as distinct from the personal problems we are discussing.) This may prove the best method but the doctors of the Unit will not, in modern times, be prepared to accept such an officer as a dictator. In each unit will be many men of senior position and sometimes of greater professional standing than the medical superintendent, and it appears inevitable therefore that the purely medical side of the service, which cannot in any case be interfered with by lay people, however elected, must be under the joint control of the whole medical and allied staff; Frequent meetings of the staff of the Health Unit will, in any case, take place, for one of the most important needs of medical men today, realisable only in a full-time service, is for meetings for the discussion of the cases passing through their hands, for hearing others tell of new discoveries or of unsolved difficulties, and for consideration of ways of improving the service. It will be for the staff to decide the running of the medical side of the Health Unit and to advise the controlling committee on its needs. This same right to discuss and advise on their part of the service must be given to all other grades, of personnel, and in the case of nurses this freedom to discuss and suggest without the presence of those dragon-like ladies, who today supervise our nurses will have widespread results in recruitment and training.

The election of representatives of the healthy part of the community is a simple matter. How are the sick to be adequately represented? The problem of “patients’ committees,” has not been discussed much in this country although in others they exist and appear to function. In sanatoria, where patients remain for a long time, it is possible to elect representatives from among the “oldest inhabitants” In some convalescent homes, where the stay is only a few weeks, committees do function, chiefly for arranging social functions but there the patients are able to walk about. So far as the ordinary hospital is concerned such a method is clearly impossible, but some form of representation from among those who have experience of the service must be obtained.

There remain unmentioned many details of organisation and administration, but enough has been said to indicate a form of service which would appear to rid us of all the disadvantages of present medical arrangements. The form of service suggested is one which detailed study shows could be as easily adapted to rural as to city areas. It aims at establishing medical service unit of such a size that it could provide economically and efficiently everything which Medicine is capable of giving, and yet small enough to be very close to and part of the active life of the community.