Former Health Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, probably Britain’s worst leader since General Percival surrendered an army of over 80,000 soldiers to 36,000 Japanese soldiers at Singapore in 1942. It was the worst ever British defeat and led directly to the dreadful Japanese concentration camps. Hunt was in charge of over a million highly committed NHS professionals with oversight of Social Care, looking after nearly a million people. He surrendered these to a succession of debilitating neo-liberal reorganisations, privatisations and defunding regimes. Like Percival he could have fought for his people, but chose not to, and England is paying a high price.

Percival’s reward was the pension of a Major General. Some think Hunt’s reward may be selected as the next Prime Minister. Think again.

Apart from his duplicity with data, his bullying of Junior Doctors, and his hypocrisy in praising the NHS and shrinking nurse’s pay, there is the question of his ability to manage. Managerial incompetence is a common trait in this Conservative government, as exemplified by Grayling, Hancock, the Prime Minister, Priti Patel and others in the Cabinet.

Hunt the manager.

In every good organisation there are key performance indicators whose sole function is to help the executive steer the organisation most effectively. In British Rail one was trains on time. The purpose was to keep the passengers safe and satisfied, as the most important need was reliability, not speed, as the politicians keep getting wrong.

A key indicator in Social Care was the performance of transferring patients from the hospitals back into their homes and care homes. The indicator was called Delayed Transfer of Care (DToC), which meant that something was preventing the patient from being discharged when they were better. It was measured by the month. It was a very important indicator, for two main reasons:

- Cost: Each time the transfer from the hospital failed on average it causes up to 31 bed delays, i.e. unavailability. The cost of this is about £400/day, compared with £90/day in a home. So each DToC generates a net loss to the NHS of at least £300×31, i.e. about £9,000. At the time of Hunt’s appointment these Social Care DToCs were averaging 1050/month – a net loss of £9.5 million per month and steady.

- Care: Patients who are well enough to go back get more ill if they stay in hospital, especially if they are elderly, thus occupying beds for much longer. They also require extra attention from busy nursing staff who are not always used to dealing with the elderly. There is also an increased risk of readmissions.

The Department of Health details reasons for these delays, 40% of which are generated within Social Care. These are the major reasons, respectively: Awaiting Care Package at Home, Awaiting residential home placement or availability, and Awaiting nursing home placement or availability. As all these delays generate extra bed demands in Acute Care as well as, so to address these immediately would be a win/win, an act of intelligent leadership, especially for an opportunist like Hunt.

Now, the bad news for Hunt: He has no organisational leadership qualities at all, especially when it comes to doing what is best for the organisation, i.e. the good of the users, the employees and the community. If he had he would have predicted a serious problem emerging in social care, and consequently a rise in the transfer of social care patients into acute care.

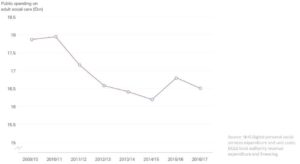

Hunt became Secretary of State for Health in 2012. At that point Care DToCs were running at 1050/month, but trouble was on the horizon. Back in 2011 Nicholson, the CEO, set the NHS and Social Care the challenge of taking out £18 – £20 billion by 2014. Why? It was a classic act of hubris which of, course, the health system paid for. It was to be efficiency savings; but how? The care system was short-staffed, underfunded and, because of the privatisation, in negative productivity. Overworked and underpaid staff, the main source of innovation, were in no position to study ways of improvement. Morale was falling and the staff turnover was 27%.

Hunt should have stopped it, but did not care, or have the nous – or else was confusing fewer staff per user as a sign of efficiency. Either way he should have kept his eye on the statistics. Social Care is a major driver of demand in the NHS. The better the care, the lower the rate of admissions into Acute Care: a very simple equation.

By 2015 there were ominous signs. The rate of DToCs was beginning to rise in a statistically significant way. The trend was clear. The average was rising to 1250, a 19% increase. Any executive worth their salt would have instituted an instant investigation. Hunt did not. His NHS 10 Point Efficiency Plan mandated the “freeing up about 2000 to 3000 beds by ceasing DTOC delays in social care.” Just like that, like Napoleon instructing his troops to conquer Moscow – winter. There was no strategy, no plan that mapped out the route. Just an edict, and like Napoleon, thing got a lot worse.

The average for the years 2016 to 2018 rose to 1900 DToCs, 80% greater than in 2012 – so much for “ceasing” DToC delays. It was not a plan but a target, and a silly one. This is worth unpacking. In five years Hunt oversaw an increase of about 900 DToCs from the Care sector alone. This is an increased loss of £8.1 million per month, or close to £100 million a year.

Just how many staff in Social Care would that have paid for at £25,000 a year? The turnover would have stopped, the facilities enhanced (including private care) and morale and user satisfaction improved.

These cold statistics disguise the misery of the people involved, nurses, carers, families and, most of all, the users, mainly the elderly. As Neil Kinnock said prophetically of the Tories if they got in: I warn you not to fall ill, and I warn you not to grow old.”

In summary, in the first three years of his appointment the total loss due to DToCs was £114 million a year. In 2015 Hunt sat on his hands, no doubt transfixed by Stevens’ unnecessary reorganisation along USA private care lines. Over the next three years the total loss would be £205 million per annum. The damage to the NHS and Social Care is incalculable. And remember we are only looking at 40% of all the DToCs, i.e. half a billion pounds a year. Much of that could have gone into PPE stock replenishment.

A final irony: In Hunt’s 2016/17 NHS 10 Point Efficiency Plan the target mandated was to “reduce Delayed Days to 4000/day, which translates into 124,000 per month by September 2018”. This equates to 4000 Delayed Transfers of Care per month across the NHS and Social Care – a figure that is actually higher (worse) than they had been achieving regularly in 2010 – 2013! But what makes it even more damning is that it was, statistically, an unachievable demand. The average for 2016/17 was 4560 DToCs and the lower control limit was 4995, which meant that statistically there was less than a 1/1000 chance that it could be achieved. Setting unachievable targets is feature of Hunt’s tenure. Caroline Molloy details these in her withering assessment of Hunt in her article What did Hunt do to the NHS – and how has he got away with it? (Open Democracy, July 13, 2019).

Matt Hancock now grasps the poisoned chalice Hunt has handed him. Luckily he is an optimist and probably sees it as a great opportunity. One day he may also be rewarded with the Chair of the Health and Social Care Select Committee like Hunt, for the utter failures, especially the disaster of his outsourcing of test and trace to private companies (0ver £10 billion), greatly exacerbating effects of the terrible Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

Dr John Carlisle

Chair, Yorkshire SHA