‘If livin’ were a thing that money could buy / The rich would live and the poor would die.’ It is, and these lines, from a spiritual temporarily made famous in the 1960s by Joan Baez, remain the best succinct description of the origins of health inequalities.

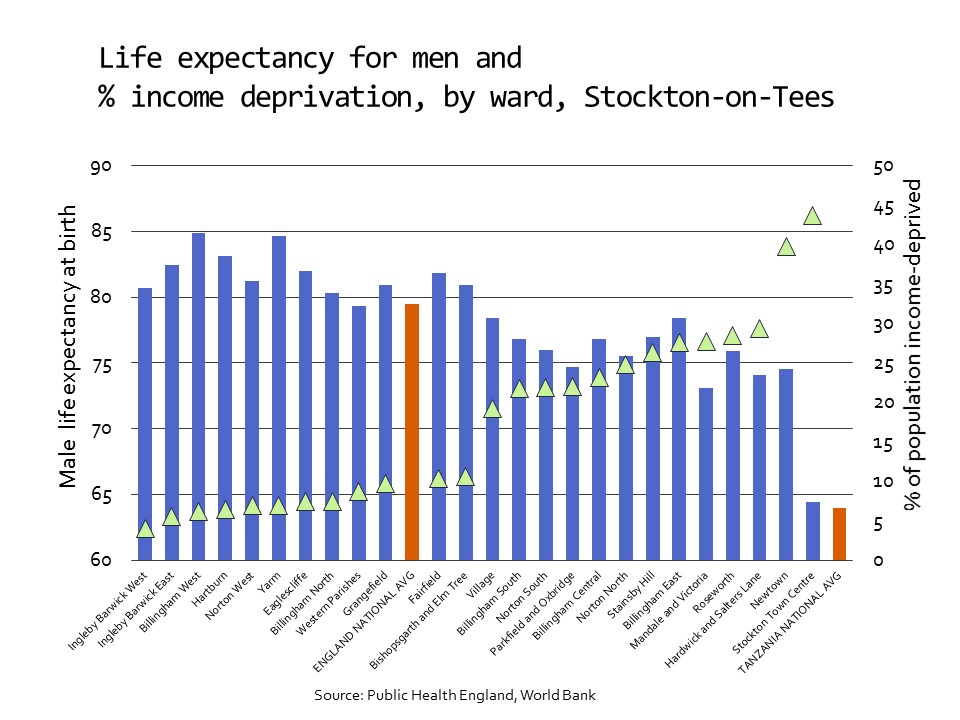

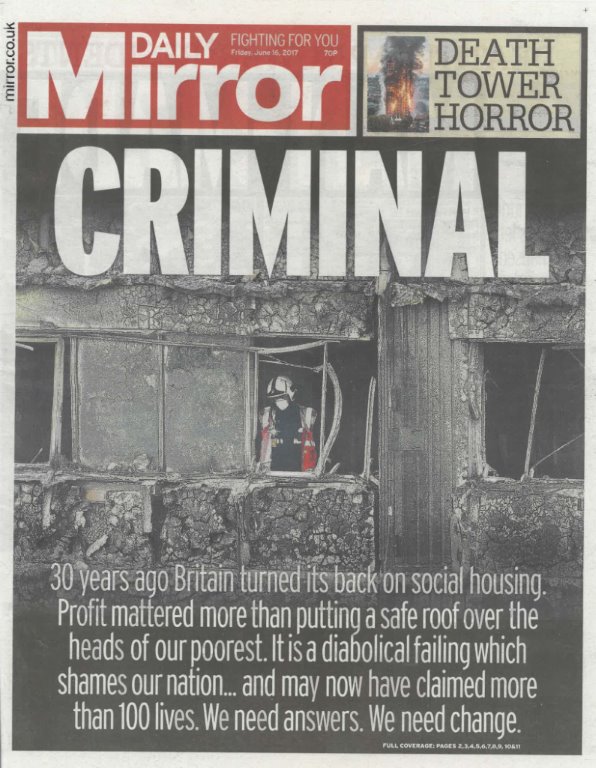

Occasionally, that reality thrusts itself into the consciousness of the high-income world, as in the case of Hurricane Katrina and the Grenfell Tower disaster. In the case of Katrina, when the hurricane hit and the levees broke (after years of governmental neglect), evacuation plans presumed that everyone had access to an automobile. Those who could afford to do so packed up the car and drove to higher ground. Others, overwhelmingly poor and African-American, were left to fend for themselves as refugees in their own country. The disposability of certain populations, from the point of view of the powerful, was similarly evident in the case of the Grenfell Tower fire, where local government in an ultra-wealthy London borough appears to have skimped on basic fire protection measures in a social housing block. Apart from high-profile disasters, the wisdom of the spiritual’s words is evident on a daily basis, although it seldom hits the headlines: in the small city of Stockton-on-Tees in the north of England where I live, differences in male life expectancy between the most and least deprived wards are larger than the national average differences between England and Tanzania.

Outside the high-income world, global health researchers and practitioners constantly confront the realities described in an article on ‘priorities for safe motherhood interventions in resource-scarce settings’. The authors wrote (in 2010) that the basic interventions recommended by WHO – still far below the standard of care that would be considered normal in the high-income world – would cost US$1.80 per person per year in Uganda, but Uganda was spending only US $0.50 per person on maternal and newborn care. So, in the health economists’ ubiquitous mantra, priorities must be set.

The researchers who carry out these exercises cannot be faulted, and there is plenty of blame to go around, starting with the fact that a decade later, Uganda’s government was still not meeting the target of allocating 15 percent of public expenditure to health that was agreed among African Union countries in 2001. But that is only part of the picture, and it is important to move beyond the familiar vocabulary of resource-scarce settings to ask why some settings are resource-scarce and others not. Those of us who do so in the academic world are considerably fewer in number than those who take such scarcities as given. We are not nearly as well funded – the Trades Union Congress and people thrown out of work when transnational corporations relocate contract production from Mexico to China do not fund a lot of research – and (no coincidence) at greater risk of precarious employment.

Nevertheless, we continue to insist that intellectually responsible answers in the global frame of reference must start with colonialism and its legacies. They must consider more recent historical episodes such as the devastating legacy of structural adjustment programmes that – according to Nobel laureate and former World Bank chief economist Joseph Stiglitz – resulted in ‘a lost quarter-century’ of development in Africa. A recent study shows that although the World Bank and International Monetary Fund abandoned the vocabulary of structural adjustment around the turn of the century, the relevant practices continue with little change. Meanwhile, the logic of structural adjustment has been replicated in the decade of (selective) austerity programmes that followed the financial crisis. Inquiries into the origins of resource scarcity must further consider such factors as the ‘disequalising’ effects of a global economic order that provides abundant opportunities for capital flight, which starves even countries with well intentioned governments of resources needed for health, education, and economic development.

In the contemporary policy environment, one element in particular connects health inequalities around the world: neoliberalism or, in the words of billionaire investor George Soros (what irony), market fundamentalism. Neoliberalism as a set of norms that guide and justify policy, ultimately equating financial worth with moral worth, conceptually links the dynamics of structural adjustment and capital flight with the fates of the victims in New Orleans and Kensington and Chelsea, and with those of working people quietly living shortened lives of desperation in Stockton-on-Tees (and other deindustrialised communities in the UK, the United States, and elsewhere). The connections are not only conceptual of course; they are also material and institutional, operating through such channels as campaign money, capital flight and the networks of power and privilege epitomised by the World Economic Forum, where the global super-elite meet to worry about the threat posed to their fortunes by the rest of us.

Tracing these connections, in contexts half way around the world or as close to home as our local NHS trust in England, is time-consuming and often emotionally draining. Yet the enterprise is essential to the larger task of demonstrating that neoliberalism is, ultimately and inescapably, deadly – a point clearly understood by at least one media outlet reporting on the Grenfell Tower fire. Well spotted, say I.

Especially when the context involves social determinants of health, the question of how much evidence suffices to demonstrate this is contested terrain. Sir Michael Marmot (who chaired the landmark WHO Commission on that topic) and colleagues wrote in 2010 that: ‘It is hard to see how even ideologically driven commentators could think that having insufficient money to live on is irrelevant to health inequalities’. This is preternatural optimism, as any observer of recent British health inequalities policy will realise, but further discussion must be left for another posting.

This first appeared on the PEAH – Policies for Equitable Access to Health blog