When Charles Frederick Thackray and Henry Scurrah Wainwright bought a Leeds retail pharmacy as a going concern in 1902, they could hardly have foreseen that their business would one day expand to employ more than 700 people, with markets all over the world. In less than a century, the corner shop was to grow into one of Britain’s principal medical companies, manufacturing drugs and instruments, and pioneering the hip replacement operation which has changed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

The story begins with Charles Thackray’s predecessor, Samuel Taylor, who came to Leeds from York as a young man in 1862. He took over a fruit and game dealer’s premises in Great George Street to set up his own pharmacy. Leeds, suffering the effects of rapid expansion caused by the Industrial Revolution, might have seemed a surprising choice for a man from York, but against the background of smoke and grime was the spirit of enterprise and opportunity.

Samuel Taylor’s pharmacy would have been familiar to Charles Thackray as a boy, as it was on the opposite corner to his father’s butcher’s shop at 43 Great George Street (then on the corner of Oxford Row), where Charles was born and where he lived until he was eleven. Charles’s father acquired three additional premises in the 1890s and business was doing well enough to enable Thackray to send his son away to Giggleswick School.

At sixteen Charles began an apprenticeship in pharmacy at the Bradford firm of F. M. Rimmington & Son. He then went to work at the prestigious Squire & Son, Queen Victoria’s official chemist’s in the West End of London, and rounded off his education with a spell working on the Continent. Thackray qualified in 1899. By this time, the profession of pharmacy had clearly emerged from traditional herbalism, a change that had begun with the creation of the Pharmaceutical Society in 1841 and the Pharmacy Act of 1852 which made provision for the Society to keep a register of chemists and druggists.1

In 1903 Charles married Helen Pearce, daughter of a leading Leeds jeweller. Their first son, Charles Noel, was born on Christmas Day two years later, followed by William Pearce (Tod) in 1907, then Douglas in 1909 and a daughter, Freda, two years after that. Charles and Helen Thackray had another daughter, but she was very frail and died when she was only ten. We can only guess at what effect the little girl’s death had on Charles, but it might go some way to explaining the ‘mental anxiety’ from which he was later to suffer.

The Thackrays lived in Roundhay, moving to bigger houses as business prospered. A man in Charles Thackray’s position would be expected to join a professional men’s club. But the obvious choice, the Leeds Club, refused him membership on the grounds that he had committed the cardinal sin of being ‘in trade’. Along with others barred for the same reason, including Snowden Schofield, founder of the Leeds department store which was to bear his name, and a couple of others in the clothing business, he set up a club of his own, which they called the West Riding Club. It had its premises on the first floor of what is now the Norwich Union building in City Square.

Much of Thackray’s time there was spent playing bridge which, along with golf, was his abiding passion. He was fond of singing, too, and the family often joined in singsongs round the grand piano at home.

Thackray’s financial partner, Henry Scurrah Wainwright, was the same age as his friend Charles and, like him, was Leeds born and bred. On leaving Leeds Grammar School at the age of sixteen, he became articled to William Adgie, Junior, at Beevers and Adgie, a leading firm of chartered accountants in Albion Street (now part of KPMG Peat Marwick). He qualified in 1899, the same year as his friend Thackray, and became a partner in Beevers and Adgie in 1905.

Wainwright, like Thackray, married a local girl, Emily White. Her father was an importer and manufacturer of botanic medicines—a herbalist rather than a pharmacist. The family business was built largely on the success of Kompo, their patent medicine for colds. Scurrah and Emily had one son, Richard, born in 1918, who was later to become financial director of the Thackray business and Liberal MP for the Colne Valley in the Yorkshire Pennines.

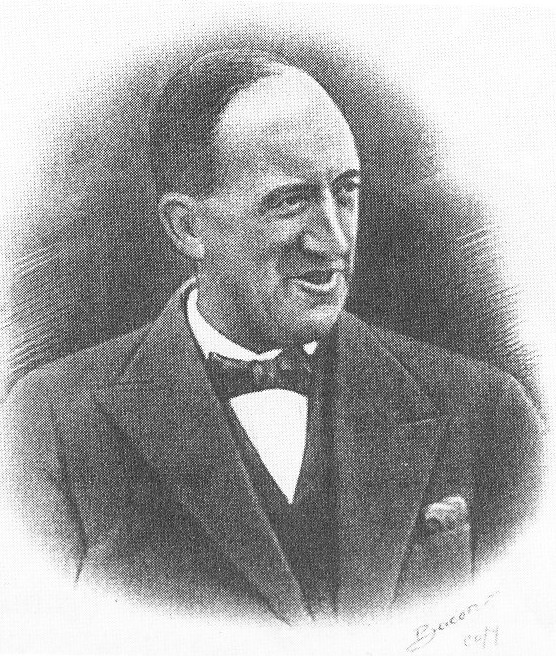

Plate 9.1 Charles Frederick Thackray, joint founder of the company and after whom the newly-established Thackray Medical Museum in Beckett Street is named.

Scurrah Wainwright was actively involved in Leeds life: he became President of the Leeds Society of Chartered Accountants, was a long-serving director of Jowett & Sowry Ltd Printers and the Hotel Metropole and was Honorary Secretary of the Leeds Tradesmen’s Benevolent Association. But it was as Chairman of the National Assistance Board’s Advisory Committee in 1938 that he was appointed Officer of the British Empire, having achieved the monumental task of interviewing every unemployed man under 30 years of age in the city in an effort to help them find jobs.

As young men, Charlie and Scurrah, as they were known to friends, lived within easy walking distance of each other’s homes in New Leeds—then a pleasant residential area on the east side of Chapeltown Road. As Scurrah’s diary for the year 1902 shows, he and Charles met at least twice a week with other friends to play cards, snooker and ping-pong in the winter and to go for walks and play tennis in nearby Potternewton Park in the summer months.

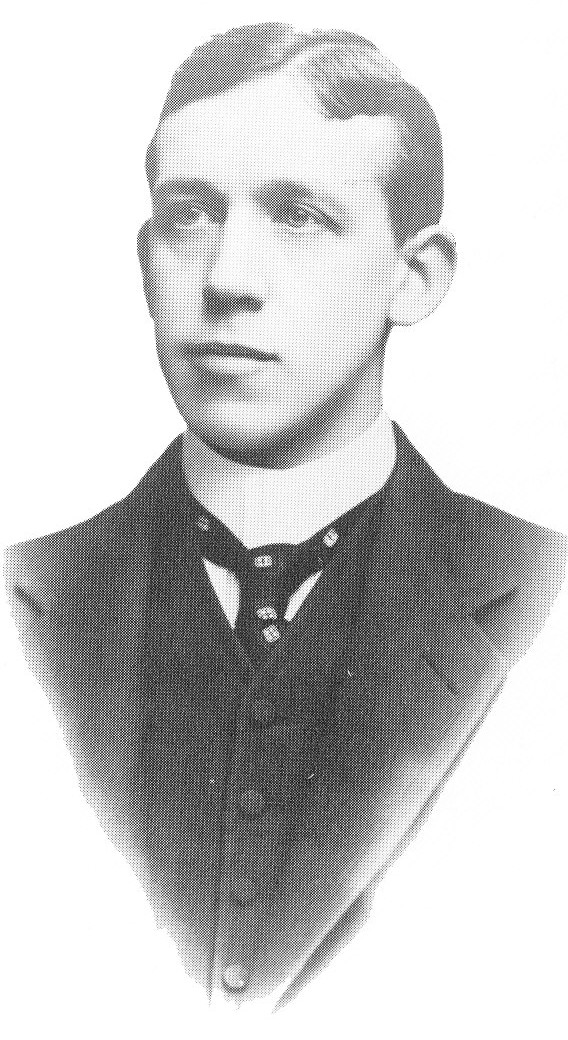

Plate 9.2 Henry Scurrah Wainwright, who with Charles F. Thackray bought a corner shop pharmacy in 1902 from which the Thackray Company grew.

It was natural that the two young men, both recently qualified in their chosen professions, should have ambitions to start their own business. They saw their opportunity when Samuel Taylor’s pharmacy came up for sale.

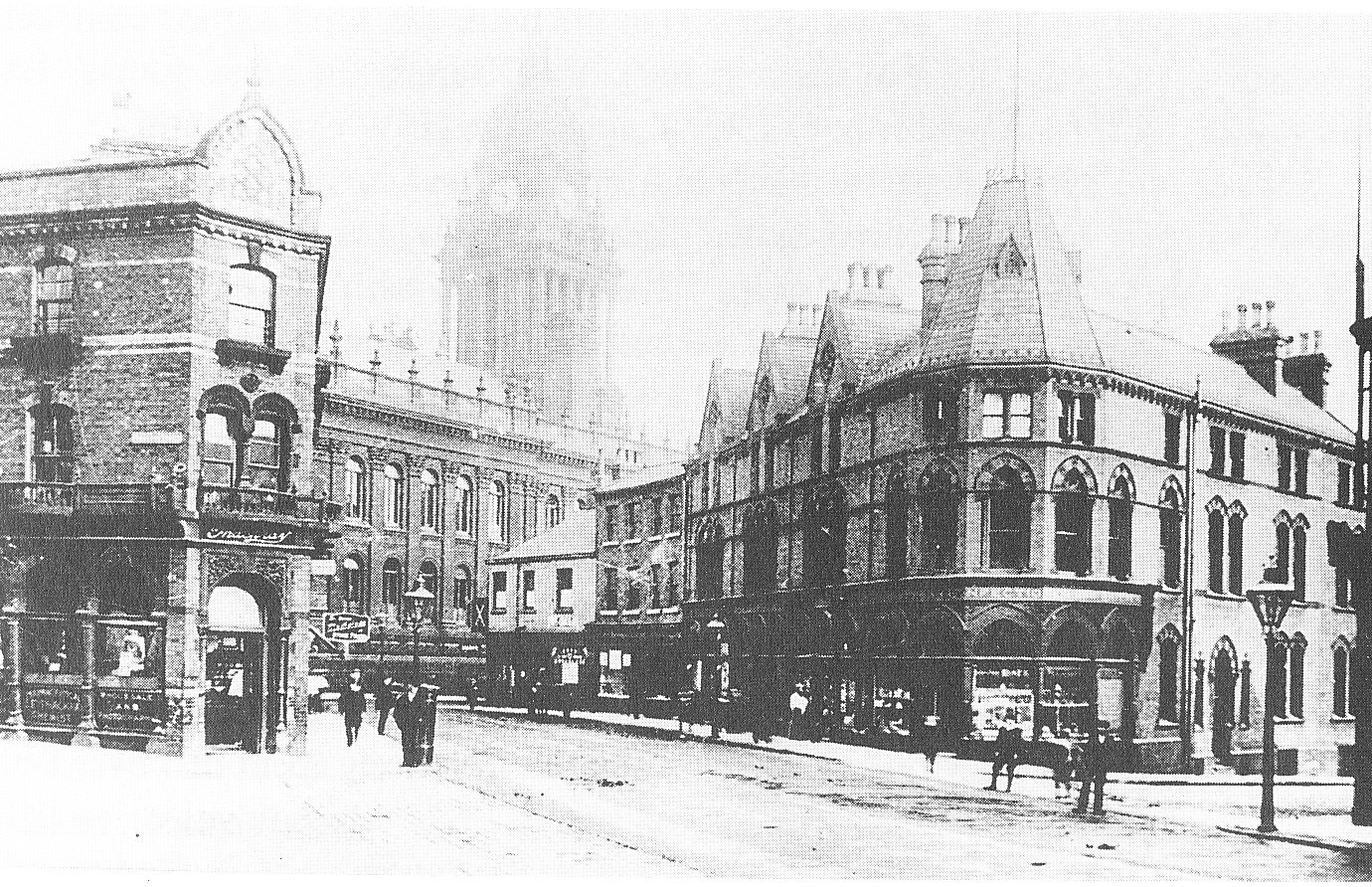

To assess its potential, as Thackray and Wainwright must have done, let us look at how Great George Street had developed since Taylor had opened his shop. By 1869 the Gothic facade of the newly built Leeds General Infirmary dominated the north side of the street—as it does today—and many medically-related businesses had grown up in the vicinity,2 including an oculist, a surgical instrument and artificial limb maker, a homeopathic dispensary, a drug company and a ‘specialist in artificial teeth’. Number 70, on the apex formed by the junction with Portland Street, was a prime site.

Many doctors at the Infirmary had consulting rooms in Park Square and would pass the shop on their way between the two. In addition, there were half a dozen private nursing homes in the vicinity, all providing potential customers. The dispensing side of the business looked healthy, too. Taylor’s prescription books between 1890 and 1901 record between six and a dozen prescriptions dispensed each day.

Scurrah Wainwright’s diary entry for Friday, 25th April 1902 reads:

‘GET arranged price of Taylor business. £900 + 13 wks at £5.’ Then on 19th May, Whit Monday: ‘GET commenced business @ 70 Great George St.’

Two days later, Wainwright records: ‘Opened bank a/c for GET. Gave him cq £100 deposit for Sam. Taylor; put £50 in his bank a/c. GET signed contract agreeing to purchase ST’s business (£900). Evg. Tennis on grass courts. 1st this year. At CFT’s shop re. books. GET stayed [at HSW’s] all night.’

Several late evenings of bookkeeping are recorded in the ensuing weeks. One evening in August Scurrah notes: ‘Saw S. [Emily, his fiancée, known as Sis], then worked late at CFT’s shop, 7.30-9.30, then with Mr A. [Mr Adgie] until 11.30 pm’. The same month a partnership was officially agreed between the pair; the original pencil draft of the agreement states that Thackray was entitled to an extra £30 salary in lieu of living over the shop.

The business traded under the name of Chas. F. Thackray. Wainwright might have added his name but for the fact that chartered accountancy was a relatively new profession and if accountants were seen to be involved in commercial ventures, their professional impartiality could be jeopardised.

Although the shop was considered to be a high-class chemist’s under Samuel Taylor’s ownership, Thackray and Wainwright immediately spent just over £40 on painting and repairs (when the buying power of £1 was equivalent to £41 today) and a further £20 on an oak bookcase, display cabinet, linoleum and an electric bell. Two apprentices were taken on in the first year, too. In all probability they lived over the shop, as was customary, to judge from food, drink and coal orders recorded in the accounts.

The first five years’ accounts show profits rising steadily, from just over £226 in 1903/4, to nearly £400 in 1907/8. They also show the first investment in equipment: £5 12s spent on a Humanized Milk Plant Separator in 1903 and £81 for a sterilizer three years later. Other purchases included a bicycle costing £2 14s, a typewriter for £7 and more than £30 on catalogue-printing.

In 1908, for the first time, profits were split two-thirds to Charles Thackray and one-third to Scurrah Wainwright, as opposed to the equal division they had shared previously. No doubt the extra income would have been welcome to Charles, now a family man with a wife, two sons and domestic wages to pay.

Advances in aseptic surgery in the early years of this century led to a new demand for sterilized dressings and instruments. The sterilizer bought in 1906 meant that Thackray could now develop another side to the business, supplying sterilized dressings to the Leeds General Infirmary, the nearby Women’s and Children’s Hospital and neighbouring nursing homes.

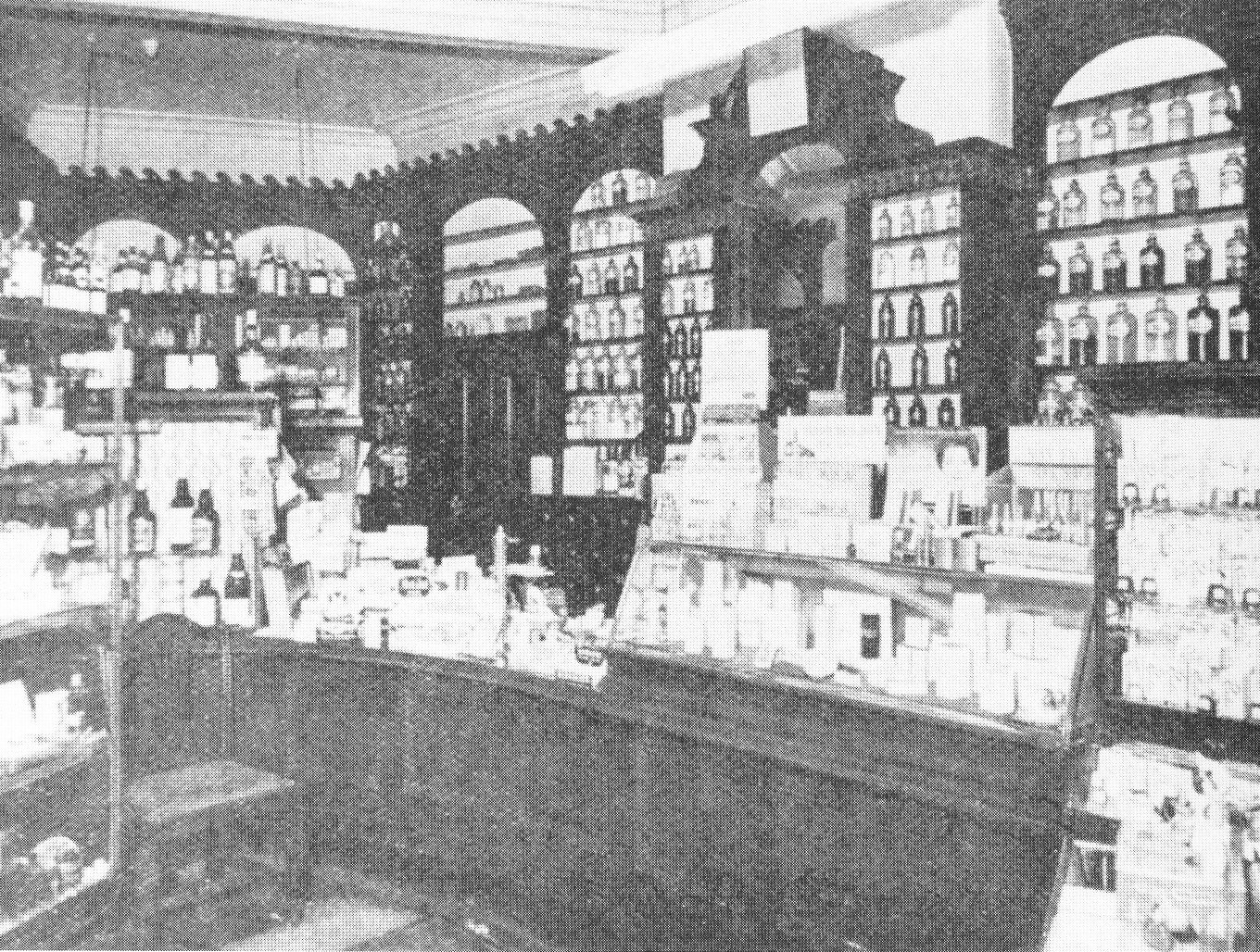

Plate 9.3 Thackray’s retail shop on the corner of Great George Street and Portland Street.

Meanwhile, common preparations such as eye and ear drops, mouthwashes, nasal sprays and cough mixtures, dispensed at a cost of between 9d and 2/6, and the occasional pair of gold spectacle frames at 8/6, were the mainstay of the dispensing side of the business. Customers represented a wide range of social class, from aristocracy (Lady Harewood’s name is recorded in the ledger for 1910) to servants.3

The first instruments Thackray sold were supplied by Selby of London in 1908. This side of the business grew so rapidly that two years later he set up an instrument repairs department in a converted stable at the back of the pharmacy. Compared to prescription fees, the income from instrument repairs was in a different league altogether.

A large number of the physicians who patronized the shop, and sent their patients there, became lifelong friends of Thackray’s and their role in his success should not be underestimated. They helped the Thackray name to become known all over Yorkshire and they played an important part in the development of the surgical instruments side of the business.

The early years of the firm coincided with major advances in surgical techniques. Leeds, in particular, was a renowned centre of high-calibre surgeons, many of whom made their names at the Infirmary; best known of all was Berkeley (later Lord) Moynihan, who achieved worldwide recognition for his contribution to abdominal surgery. It was Moynihan who first suggested to Charles Thackray that he should make instruments; and the firm, with its experience in repairs at their premises just across the road, was well placed to do so.

In 1908 Thackray bought the firm’s first powered transport—a Triumph motorcycle—and advertised for the first time in a national magazine. He also took on his first representative. By 1914, he had taken on two more, marking the beginning of a shift in emphasis from retailing towards wholesaling.

Although the firm enjoyed regular orders for drugs and equipment from Yorkshire hospitals, they had to break into long-established names in the field if they were to expand. Thackray’s insistence on employing only qualified pharmacists as salesmen resulted in a salesforce well above the average—and went some way towards overcoming any prejudice surgeons might have in talking to a sales representative.

By the outbreak of the First World War, turnover was about six times that of the first financial year. Thackray’s was employing 25 people, including eight instrument makers and three full-time representatives. Salesmen visited customers over a wide area, supplying wholesale pharmaceuticals not only to hospitals and nursing homes but also to general practitioners serving rural areas. Where chemist shops were few and far between, doctors did much of their own dispensing and therefore carried stocks of common medicines with them.

The First World War brought with it an increased demand for dressings, many of which were sewn on to bandages by hand in those days. Thackray’s, looking to boost their production and not afraid to pioneer new methods, bought a machine which made the ‘Washington Haigh Field Dressing’ cheaply and quickly. Acceptance by the War Office of Thackray’s ‘Aseptic’ range as standard field dressings was important to the firm, both ensuring large contracts for drugs and sundries and, to a lesser extent, instruments. Ministry approval also provided a useful testimonial for potential customers.

The Infirmary continued to place regular orders with the firm and in 1916 the hospital ordered sterilizers to equip its new operating theatres in the King Edward Memorial Extension.4 The total for ten items, including water, instrument and glove sterilizers, dishes, copper cylinders and a cylinder sterilizer, came to more than £500 (worth about £17,500 today). The following year another substantial order was placed for theatre furniture, totalling £487. Instrument repairs for the hospital continued to be undertaken by Thackray’s at least until 1926, after which the Infirmary’s accounts stopped being itemized.

By the end of the war in 1918, Thackray’s employed fourteen instrument makers, out of a total workforce that had risen to 32. The surgical equipment supply side of the business prospered, largely owing to the increase in surgery in Leeds and Thackray’s realization that there was a limit to the amount of wholesale drug business that could be obtained from doctors.

The sales area for instruments now became greatly extended. Consequently more representatives were taken on and organized into a sales team. Unlike most, Thackray’s salesmen were not paid on commission, but given a share of the profits, a practice which encouraged them to win their contracts on the most favourable terms for the company. Thackray’s reputation in the trade for having a first-class sales network throughout the UK won them important distribution rights and they acquired agencies for various American products, then in advance of home-grown equipment in terms of design and gadgetry.

The US company Davis & Geek, who manufactured soluble sutures and surgeons’ gloves, saw Thackray’s as an ideal distributor for their products. The sutures were Thackray’s first national distributorship. They were a superb product and were to be both profitable and good for the firm’s reputation. In due course, films were made of classic surgery being done with Davis & Geek sutures, and representatives were each equipped with a Kodak home cine projector to use with hospital audiences. Davis & Geek’s parent company, Lederle, front-runners in the 1920s in the production of serums for measles, whooping cough and other infectious diseases, also asked Thackray’s to act for them throughout the UK and provided, at their own expense, three or four more representatives for the purpose. Later, when sulphonamide drugs were introduced, Lederle again made Thackray’s their UK distributor.

By the 1920s, the firm’s changing emphasis from Pharmaceuticals and dressings to surgical supply brought rapid expansion, and Thackray’s outgrew its Great George Street premises. By 1926, employees had doubled in number since 1914.

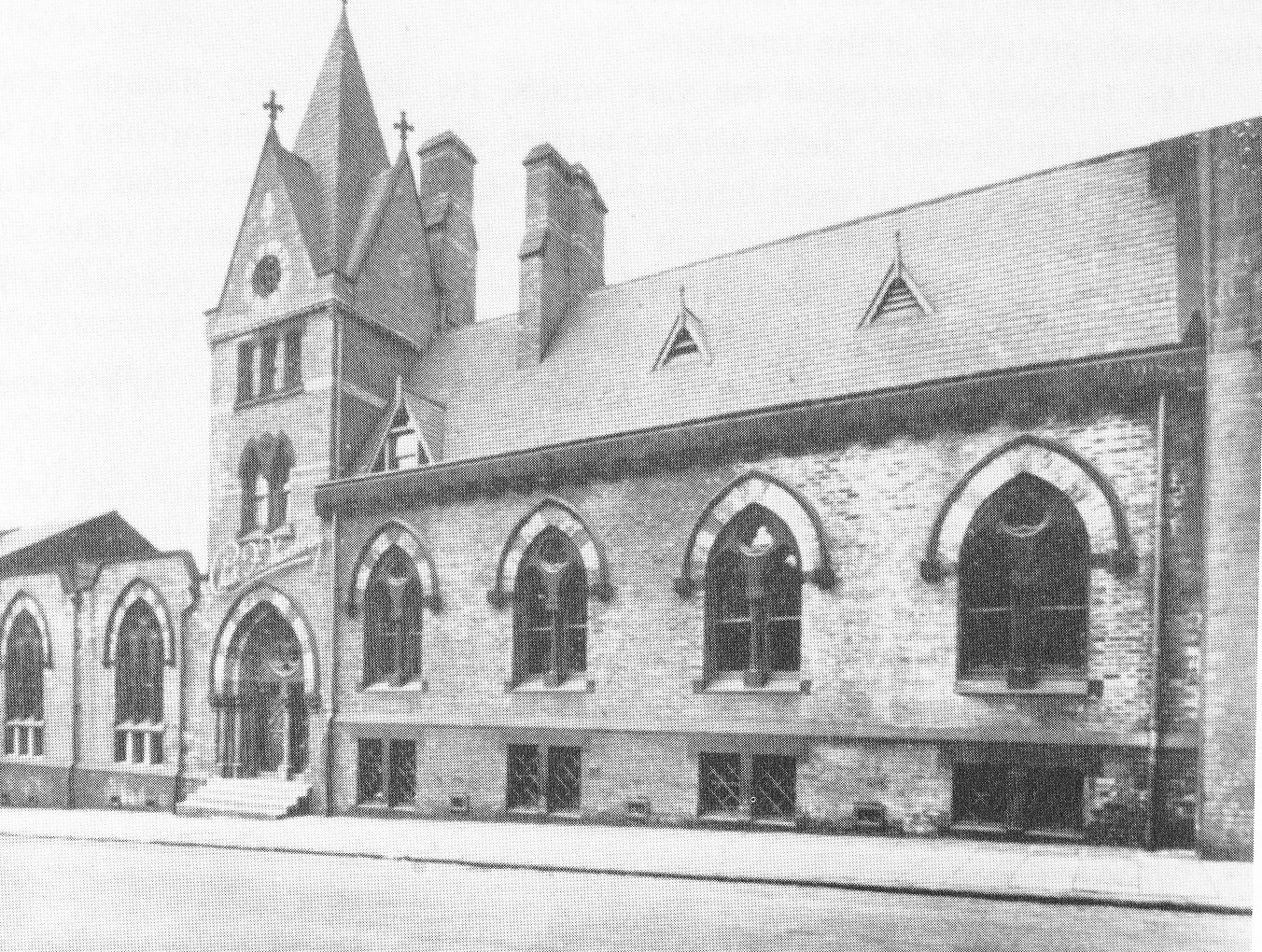

Plate 9.4 The offices and showrooms of Chas. F. Thackray, formerly the Old Medical School, Park Street, Leeds.

Thackray was fortunate to find the extra space he was looking for just round the corner in Park Street where the Yorkshire Archaeological Society and the Thoresby Society (the Leeds historical society) occupied the Old Medical School. The Park Street building had been purpose built in 1865 for the Leeds School of Medicine.5 In the intervening years, it had been sold to the Yorkshire College of Science, precursor of Leeds University, then to the two historical societies. So when Charles Thackray made an offer the Societies considered ‘too good to refuse’, it was appropriate that it was to have a medical use.

When Thackray’s took over the building in 1926, a lot needed doing to it. After alterations and repairs totalling more than £3,000, administration and most of manufacturing could be transferred to the new premises. Number 70 Great George Street was retained as a retail pharmacy and for the manufacture and fitting of surgical appliances.

Early days at Park Street are remembered clearly by staff who worked there:

“I left school at fourteen and joined Thackray’s in 1928. I used to pack parcels and take them on a handcart to the post office in Park Square. Often the wheels got stuck in the tramlines.”

‘Mr Thackray impressed me very much. He was a very likeable chap, always smartly dressed. There was no barrier with him. It was nothing to see him take his coat off to wash bottles—Winchesters, they were called, holding three or four pints—in the basement. I remember he had a massive office with a massive desk in it; a contrast to the petite person who sat behind it. He travelled in a chauffeur-driven limousine, an American car.’

Though approachable, Thackray demanded high standards. As a sixteen-year-old apprentice in 1932, another employee recalls:

“I was scraping enamel off a trolley to be re-enamelled—this was before the days of stainless steel—and Mr Thackray came to inspect the work. He asked for some paper to be spread on the floor and he went on his hands and knees so he could check the underside of the trolley…I finished my apprenticeship when I was twenty-three.’

A thorough training by any standards, but the firm’s reputation was built on first-class workmanship. It is fair to say that Thackray’s was rated as one of the best employers in the Leeds area, an essential element in the production of high-quality instruments. (Even during the Depression years of high unemployment, Thackray’s was able to offer a 58 3/4 hour working week for engineers, compared to the average 513/4.6) It is equally fair to say that the staff were exceptionally loyal and formed a closely-knit team who were willing to put themselves out on their employer’s behalf when necessary.

“At holiday time, Whitsuntide and Easter, the firm closed for the Monday and Tuesday. We worked with a skeleton staff and one director on the Tuesday to open the post and despatch any urgent orders.”

‘Once, we had an order for six sterilizing drums—they’re about fifteen inches tall and a foot wide—at Harrogate. The director on duty had a sports car. It was raining and, with the drums piled in my lap, we couldn’t shut the roof, so we were wet through by the time we arrived. But you didn’t mind.’

Recruitment of staff by recommendation rather than by advertisement meant that there were many instances of people from the same family working for the firm. A lively calendar of social events meant that everyone knew each other, whichever department they belonged to. A Social Committee, started in the 1930s and funded by weekly subscriptions and raffles, organized dances, outings and whist drives. It arranged cricket and golf matches with local organizations and started a football team which played at Roundhay Park.

The Thackray football team competed in Sunday Combination League matches; success in a rather different league was achieved by Jim Milburn, the former ‘iron man’ of Leeds United and uncle of the famous brothers Bobby and Jackie Charlton. He worked as a labourer at Thackray’s from 1966 to 1982.

The 1920s had seen sales in the home market flourishing. Turnover in wholesale Pharmaceuticals was brisk and increased instrument sales led to the opening of a London depot in Regent Street. Now Thackray turned his attention overseas.

Much of surgery round the world at this time was British because Empire countries sent trainees and postgraduates to the UK. Therefore British products sold well in Empire countries and where there was a strong British influence, such as Canada, Australasia, South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria.

To begin with, Thackray’s sent its own manufactured surgical instruments chiefly to the Mediterranean, the Middle East and West Africa; the firm were buyers for the Crown Agents, whose job was to buy for the Crown colonies. In those days, salesmen went on trips lasting, perhaps, six months, or up to two years. By 1930 the yearly total for exports was nearly £6000, about one-thirtieth of total turnover. Markets had been built up thanks chiefly to substantial leaflet advertising and to the increasing renown of the ‘Moynihan School’ of surgery.

Thackray’s staff had increased to 100 by 1931. Since 1914 the firm had trebled its production and increased its turnover eightfold, despite generally slack trading conditions in most of the economy. Then international financial problems and a world slump led to devaluation of the pound. With fewer goods imported, it was opportune for Thackray’s to expand its own manufacturing capacity.

In the early Thirties the firm therefore began to make its own hospital sterilizers, operating tables and other items of theatre furniture. Packed ready for despatch, storage became a problem. Cases were stacked on stairways and in passageways; even in the front entrance sometimes.

To make room for the extra manufacturing activity and storage at Park Street, the entire rear half of the building was demolished in 1933. It was then rebuilt to three storeys as a modern building of the time, with a fourth storey added shortly afterwards. The neo-Gothic front façade remained more or less unchanged.

Although the firm rode the Depression years well, it suffered a major blow in 1934 when Charles Thackray died suddenly at the age of 57. He failed to return from an evening walk in Roundhay Park near his home and later his body was recovered from Waterloo Lake.

His widow, Helen, had witnessed his mental anxiety for the previous two years and felt that his death would at last have given him peace. A tendency to anxiety that seemed to run in the family and the effects of his young daughter’s death were both likely to have affected Charles’s mental state. Nowadays, his condition would probably be diagnosed as anxiety neurosis.

Thackray died when the two (of his three) sons who had joined the business were relatively young and inexperienced. Noel was twenty-nine and his brother, Tod, twenty-seven. The man best placed to take up the reins was Mercer Gray; he had been with Thackray’s since he was a newly qualified pharmacist before the First World War, and had become the most senior manager in the firm.

Ownership of Charles Thackray’s share of the firm passed to Noel and Tod, and Helen Thackray was given financial security with an allocation of preference shares. (The business had grown by this time to achieve annual sales of about £200,000, equivalent to over £5million today). It was agreed that a limited company should be formed, with Scurrah Wainwright as Chairman, Mercer Gray as Managing Director and Noel and Tod Thackray as Directors of the Commercial and Manufacturing operations.

The Thirties continued to be formative years in the field of surgery and Thackray’s were designing and making an increasingly wide range of instruments. It was therefore essential that the firm produce a comprehensive catalogue to replace the handful of leaflets (not to mention competitors’ catalogues) they had relied on to date. In 1937, under Mercer Gray’s direction, two volumes containing line drawings of every instrument Thackray’s supplied were made available for the first time.

Many instruments were made to surgeons’ own specifications—witness the number named after their inventor in any Thackray catalogue index. The close co-operation between surgeon and manufacturer shows up in the firm’s correspondence, such as this letter from Mr Cockcroft-Barker, MB, ChB, writing to Mercer Gray in 1938 about a dilator: The true secret of the instrument,’ which is not easy to decipher owing to Mr Cockcroft-Barker’s handwriting, ‘is the curve and also the length of the dilating portion.’ He suggests to Mercer Gray in a post script that this ‘might be a good thing to keep up your own sleeve’.7

Surgeons could come to Park Street to buy their instruments; they could also get to know of new products at medical exhibitions. Thackray’s claims to have been first in its field to run an exhibition in conjunction with a surgeons’ meeting—a practice that is widespread nowadays with clear advantages to both parties.

The pre-war instrument catalogue lists about 2500 different items (at least twenty of which were to Moynihan’s design). Park Street, where all design and the majority of manufacture took place, had become totally inadequate.

A new factory would have to be reasonably nearby, so that the Managing Director could travel to the works easily; it should not be too expensive, and should be capable of expansion. A site fulfilling these criteria became available at Viaduct Road, about a mile to the west of Park Street.

As a result of the government’s wartime policy of concentrating industry to make best use of resources, Leeds Dyers, to which Scurrah Wainwright was financial adviser, were looking for a buyer for their textile dyeing works. The three-storey building, alongside the River Aire and the Leeds-Liverpool Canal, was old but solidly built.

While the Viaduct Road site accommodated increased instrument manufacture, production of pharmaceuticals and dressings continued at Park Street. Drugs were produced in what was known as ‘the lab’, although it would hardly be recognized as such today.

‘We used to prepare 20, 40 or even 80 gallons in large barrels stood on the floor. The mixtures were stirred with a big pole, filtered through asbestos and ladled by hand into buckets before being poured through funnels from the top of steps into smaller barrels,’ recalled one member of staff.

The retail shop, meanwhile, dealt in smaller quantities. Apart from one or two stock items, such as cough mixtures, aspirins and ‘Thackray’s Pile Pills’, most preparations were made up individually from doctors’ prescriptions.

A visit to the doctor was expensive for many in these pre-NHS times, so the pharmacist played a much more important role in diagnosis and treatment than his modern counterpart. Often, the customer would take the recommended remedy while still in the shop, sitting on one of two chairs provided. This practice could have its drawbacks. On one occasion, a customer came in complaining of queasiness and was given—reasonably in the circumstances— a seidlitz powder, a common remedy for indigestion. The customer drank the mixture and promptly keeled over and died. In fact, the man had suffered a heart attack and the pharmacist’s action was not to blame.

The shop enjoyed a reputation as a high-class chemist; Thackray’s maintained their policy of dispensing only private prescriptions, even after the introduction of the National Health Service. A high standard of service was maintained by a level of staffing that would be unthinkable today. Under the Manager were an Assistant Manager, two unqualified staff who dealt with nursing home orders, four apprentices, four errand boys and two cleaners. The shop was open every day of the year, including Christmas Day. Weekday closing at 7 pm (an hour earlier than many other shops in Leeds) meant that apprentices, whose evening classes began at 6.50 pm at Leeds Central School a little further up Great George Street, had to sprint up the road after closing time.

Plate 9.5 The interior of the Great George Street pharmacy.

The Second World War inevitably created high demand for drugs, dressings and surgical instruments, with injured servicemen returning to Britain for treatment. Among the worst casualties were the burns suffered by airmen shot down in the Battle of Britain. Many of these young men, who included Canadians, Australians, Poles and Czechs, as well as Britons, were taken to East Grinstead hospital in Sussex—one of only four plastic surgery units in the country— which was under the direction of the gifted surgeon, Archibald Mclndoe.8 He was Consultant in Plastic Surgery to the Royal Air Force and was later knighted in recognition of his pioneering work. At East Grinstead, Mclndoe wrought miracles of reconstructive surgery; through this work he became a household name. It was Thackray’s who made many of the instruments for this delicate surgery, including dissecting forceps and scissors to Mclndoe’s own design.

The fact that Mclndoe did not take his business to London firms—which, after all, would have been a more obvious choice for a surgeon based in the South East—underlines the importance of Thackray’s maintaining a presence in the capital: although it was expensive, they had to be seen as a national company, not just a provincial one.

Without the London office, it is unlikely that Thackray’s would have been in plastic surgery at all. As well as fostering links with surgeons at the plastic surgery centres in the South East, the London representative won profitable accounts from major London teaching hospitals. The significance of instrument sales such as these was that orders for other Thackray goods tended to follow.

One of the craftsmen who worked from surgeons’ backs-of-envelopes sketches for instruments turned his skill to providing life-saving equipment to servicemen who were to be dropped by parachute across the Channel. Folding scissors, saws and wire cutters were fitted into the heels of boots, compasses were hidden in tunic buttons and Gigli saws (a flexible saw rather like a cheese-cutter) were concealed in coat collars.

Many members of staff were called up into the forces. Some of the older ones volunteered to join the Home Guard, and came to work in battledress, while at the retail shop, two firewatchers took turns to sleep on the examination couches in the orthopaedic department.

The war brought a big influx of women into the firm, to train for jobs that men had had to leave for service duties. (The foundations of training laid in the war later grew into an Apprentices School, created in 1961 out of the difficulty in recruiting suitably qualified labour, especially in connection with surgical instrument manufacture, which was more of a craft than light engineering. Latterly, sixteen-year-old school leavers served a four-year apprenticeship, of which the first year was spent at an Industrial Training Board college and the remaining three completing work experience at Thackray’s.)

Hand work represented a large proportion of activity during the war and even into the 1950s. Some of the young female employees did a range of jobs: ‘We used to roll up catgut [for sutures] and put it in envelopes. My least favourite job was in repairs. Broken glass syringes came in, sometimes still with blood on, and we had to knock off the broken glass with hammers.’ Other duties included plaiting horsetail hair in groups of a hundred and cutting and rolling bandages from a large piece of lint. Today, it seems surprising that even as late as the 1950s so many jobs were carried out by hand, but the business—in common with the rest of the trade— had been traditionally craft-oriented; it was not until the 1960s that this labour-intensive approach was gradually modified in favour of more highly mechanized production.

The closing years of the war saw the development of antibiotics, which was radically to change the treatment of a host of illnesses. Thackray’s was awarded the important new distributorship of one of these, Sulphadiazine, developed by the pharmaceutical firm May & Baker (M & B). Vaccines, too, were undergoing major advances. Soon after the war, Thackray’s were carrying stocks of Lederle’s new measles vaccine with approximately four times the potency of its predecessor. Such agencies were highly profitable: turnover for the Lederle account in 1946, for instance, was almost equal to the firm’s total exports.

The introduction of the National Health Service in 1948 was the most important single factor to affect Thackray’s after the war. The Ministry of Health took over all voluntary and municipal hospitals, and the extensive re-equipping that followed led to a busy and expansive period for all sections of the business. (The Leeds Postmaster remarked that Thackray’s generated one of the biggest parcel posts in the city.)

Service has been described as the lodestone of Thackray’s. The firm had already established a depot to facilitate distribution in the South of England; now another was needed to supply Scottish customers promptly, and Glasgow was chosen for a second warehouse. At this time, too, a South African subsidiary was created, initially based in Cape Town. As a prosperous dominion, South Africa offered a potentially lucrative market, with the additional advantage that it had no major UK competitors.

Exports, slowed during the war, began again in earnest immediately hostilities ended. Yearly total export turnover, averaging about £50,000 during the war years, leapt to £120,000 in 1946 and continued to rise in the 1950s. Thackray’s sales force was once more increased, with some representatives travelling overseas full-time.

The life of the overseas rep. was not always as glamorous as some of the exotic destinations might suggest:

‘On one occasion, in Sierra Leone, the booking clerk at a rest house told me I would have to share a room. I not only shared a room, but a bed—with an American agronomist.’

It could be dangerous, too. One overseas representative contracted cerebral malaria in Africa, another tells of a narrow escape when caught in crossfire in Venezuela.

A less hazardous way of promoting Thackray’s products was participation in international trade fairs. Frequently, orders for equipment would be taken at the exhibition stand but sometimes the fairs were not so much of benefit from a commercial point of view as to show the flag, encouraged by government subsidy.

In 1956 Mercer Gray died and the second generation of the three families involved in the Thackray business now assumed new responsibilities. Mercer Gray was succeeded as Managing Director, jointly, by Charles Thackray’s sons, Noel and Tod. Richard Wainwright and Mercer Gray’s son, Robert, were elected to the Board the following year. A family firm, such as Thackray’s, presents special problems regarding its future financial security when share ownership is divided among the families involved. To avoid the pitfall of being forced into a sale by death duties, the heads of family had established family trusts, making over some of their shares to trustees for the benefit of their children. Although commonplace nowadays, such arrangements were then quite innovative and meant that the company weathered without difficulty the financial consequences of Mercer Gray’s death—and, later, Scurrah Wainwright’s and Noel Thackray’s.

Noel and Tod took over the managing directorship of the company in the climate of post-war prosperity. Manufacturing continued to increase and the firm once again outgrew its premises. Unable to expand at Viaduct Road because it was discovered that there were major sewers underground, the company looked elsewhere. A factory in St Anthony’s Road, Beeston, in South Leeds, was up for sale. Although it had more space than required at the time, Tod Thackray was convinced that they should buy the site. He persuaded fellow directors and the Beeston factory was acquired in 1957 at a cost of £55,000 (equivalent to just over £600,000 today). It has proved to have been a shrewd investment in the light of subsequent expansion.

Manufacturing and drugs moved to Beeston and the now-empty Viaduct Road building was put up for sale. It failed to attract a buyer, however, owing to a proposed plan to straighten a dog-leg bend in the road adjoining the factory (a plan which was never carried out). In the event, therefore, the Drug Department, together with the Wholesale Pharmacy, took over the premises. The removal of the instrument works from Viaduct Road was not without drama. A young man who had been employed at the works had been convicted of murder in 1945, a crime passionel, it seems. The victim’s blood stained clothing was only discovered twelve years later, when machinery was unbolted from the floor for removal.

Thackray’s expansion in Leeds was followed by the acquisition of two specialist manufacturing companies, the British Cystoscope Co Ltd, in Clerkenwell, London, and Thomas Rudd Ltd of Sheffield, makers of surgical scissors. What both these companies had in common was a highly skilled workforce producing instruments to the exacting standards required of Thackray products.

Although most sections of the business had been expanding throughout the 1950s, changes in the pattern of medical practice brought about by the National Health Service had led to a decline in business at the retail shop in Great George Street. Prescriptions from nursing homes and physicians with practices in Park Square, on which the trade of the shop had depended in the past, had declined; at the same time, profit margins on products had dwindled so that the shop was not even covering its overheads.

Despite its popularity among customers, the Board could not ignore the shop’s balance sheet. In January 1962, it served its last customers, sixty years after Thackray and Wainwright had started their business there and a century since it had begun as a pharmacy under Samuel Taylor’s ownership.

In general, however, the post-war reconstruction period of the 1950s and 1960s was highly profitable for the medical business, with large sums of public money directed towards new hospitals and universities.

In 1961, for the first time since the National Health Service had come into being, Regional Hospital Boards were encouraged by the Minister of Health to make long-term plans for hospital building, with an allocation of more than £60 million capital expenditure for 1961-3 and further sums forthcoming by the mid-Sixties. This new attitude towards health spending virtually guaranteed Thackray’s a fast-expanding home market for the Sixties and made a sound base for increasing export trade.

The 1960s were notable, too, for the important association Thackray’s developed with a remarkable surgeon whose name was to become as famous as Moynihan’s and Mclndoe’s. John Charnley, later knighted for his work in the field of total hip replacement, was an orthopaedic surgeon at the Manchester Royal Infirmary when he had first asked Thackray’s to make instruments for him in 1947 as an alternative to a long-established London firm.9

However, his most notable collaboration with the firm concerned total hip replacement, an operation to reduce pain and restore movement to the hip by implanting a manmade replacement for the deteriorated ball-and-socket joint. Briefly, the artificial hip (or prosthesis) comprised a ball-ended stem which fitted into the patient’s thigh bone and a cup which took the place of the socket (or acetabulum) in the pelvis. Charnley refined his hip replacement operation throughout his long association with Thackray’s and was still working on improvements when he died in 1982 at the age of seventy.

The close collaboration between surgeon and manufacturer is revealed in Charnley’s copious correspondence with the firm.10 Sometimes he would write three or four letters in a week, concerning himself with everything from the minutiae of design to broader, commercial issues. He was without question a perfectionist and could be forthright in his criticism of Thackray’s, but he was quick to apologize, too. Thackray’s, though tolerant of his demands, could reply with equal vigour and an understanding developed between them.

In the pioneering days of the operation soon after the Second World War, Thackray’s made the stainless steel stems, while Charnley made the sockets himself, turning them on a lathe in his workshop at home.

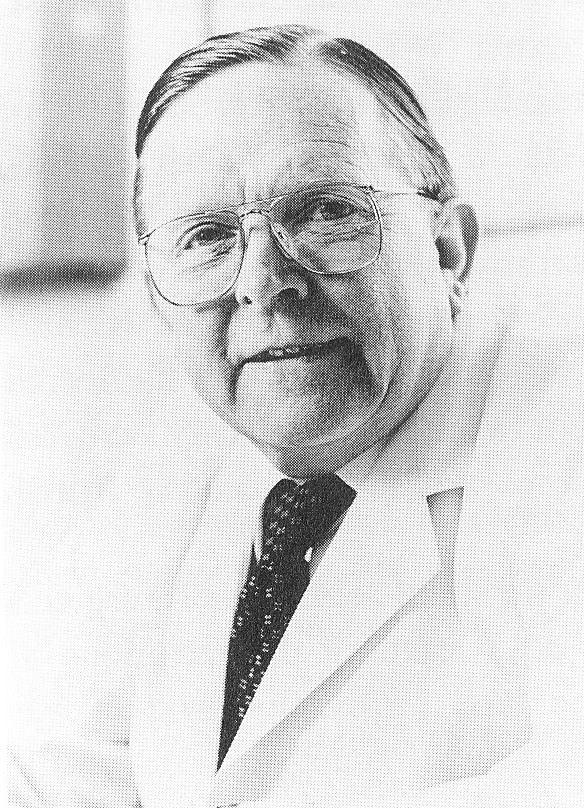

Plate 9.6 Sir John Charnley, knighted for his work in the field of total hip replacement, who collaborated with Thackray’s from 1947 until his death in 1982.

This arrangement continued until 1963, when Thackray’s took over the socket production. Interestingly, the most suitable material Charnley found for the sockets was Teflon*11, better known for its non-stick properties in cooking pans.

Charnley had set up his own workshop in the 1950s at the Wrightington Hospital near Wigan where he was Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon. His technicians made instruments under Charnley’s close supervision and then Thackray’s manufactured them. As time went on, Thackray’s contributed their own design suggestions; this continual exchange of ideas was a significant factor in the advance of the hip operation.

By 1962, it became evident that Teflon was not the ideal material for replacement sockets. Charnley was impressed by a new material, a high molecular weight polythene, which he—characteristically—tested by implanting a sample in his own thigh. Only with no reaction discernible after six months did he begin to use the new material with patients.

However, he was worried that other surgeons would take up his operation before the new material had been proven. Even after five years, he allowed Thackray’s to sell only to those surgeons whom he had personally approved— although the special instruments were available because they could be used for other hip operations. Such a restriction often put Thackray’s in the embarrassing position of having to refuse requests for Charnley implants from eminent surgeons.

Charnley’s caution did not prevent considerable demand for the product, however, and the surgeon berated Thackray’s for not manufacturing in sufficient quantity. They responded by improving their manufacturing capability, so that by the end of 1968, they could write:

‘As from January 1st next, we shall increase our rate of production of prostheses by 25% and our anticipated production will be 6000 per annum, which could be increased to 7000 by the end of the year. Additional production up to 10,000 per annum could be organized without too much difficulty.’

Although the mechanics of the hip replacement operation had become established in the 1950s and 1960s, recovery in some patients was hampered by infection in the wound. With Charnley’s encouragement, Thackray’s created a model ‘clean’ area for the packing of prostheses, not simply meeting British Standard requirements but setting them.

In due course, Charnley stopped making a personal selection of surgeons and any who had spent a minimum of two days learning the technique at Wrightington could buy his prosthesis. By the early 1970s, the product was made generally available and Thackray’s were fully stretched to produce the quantity of Charnley hips and instruments required.

It was at this time that Noel Thackray died. The consequences of Noel’s death are described in more detail later but, in essence, it led to a reorganization of the firm’s management with Tod Thackray taking over his brother’s role as Chairman and becoming sole Managing Director. Tod’s son John became Deputy Managing Director and his nephew Paul (Noel’s son) was appointed Director responsible for Interplan Hospital Projects and much of the company’s purchasing activity.

The changes coincided with a period when government was encouraging industry and universities to collaborate in order to make full use of the most up-to-date techniques available. In this context, Thackray’s approached Leeds Polytechnic Industrial Liaison Unit for advice on how to meet their increasing production demands. Accordingly, a general works manager was appointed in March 1971 and, shortly afterwards, Ron Frank, the management studies lecturer who had produced the works organization report, joined the company. Significantly, these two were the firm’s first professionally trained managers from non-medical industry.

At the time they joined, manufacturing was craft-oriented, employing highly skilled men who could turn out excellent products. However, such craftsmanship had two inherent drawbacks: there were difficulties in achieving precision consistency and there was little flexibility of volume. The 1970s consequently saw major capital expenditure in machinery. Computer-controlled, and operated by only one technician, the new machinery could turn out large numbers of stems (50,000 a year in 1990) and a sophisticated electro-chemical process honed the metal to a high degree of accuracy.

By far the biggest expenditure, however, was in equipment for ‘cold-forming’ steel. This process—whereby steel is compressed between dies at much lower temperatures than conventional forging—could dramatically increase the strength of stems without enlarging them. Although the incidence of stems fracturing in patients was extremely low, Thackray’s continuously researched stronger materials. A new steel was developed, called Ortron 90*.12 It was calculated to prolong the life of the implant so that no further operation would be necessary during the patient’s lifetime. It also allowed Charnley to develop a new, narrow-necked stem.

Demand for Charnley products was high and took the company into new export fields. In the US, Thackray’s was faced with building up sales against giant competitors; the volume required presented problems, too, and in 1974 an American company was granted an option to manufacture Charnley hip prostheses and sockets.

What made Charnley’s contribution to orthopaedics exceptional was the combination of his undeniable skill with his gift for innovation and the will— including, as he admitted, acting as ‘the scourge and flail of Thackray’s’—to see it through. He was given due recognition in the citation that accompanied the honorary Doctorate of Laws awarded to Tod Thackray by the University of Leeds in May 1988:

‘He and his company have contributed to some of the greatest advances in orthopaedic surgery this century. Through his long co-operation and friendship with the late Sir John Charnley, Mr Thackray and his company confronted and overcame some of the major problems in orthopaedics….Though a skilled engineer as well as a surgeon, Charnley quickly outran the resources of his own laboratory and it was through his close co-operation with Thackray and his company’s engineers that low-friction total hip replacement was gradually perfected.’

By the time Charnley died in 1982, thousands of hip replacements operations were carried out annually. A huge number of implants therefore needed to be available. An exact fit for each patient would have necessitated keeping in stock literally hundreds of different designs and sizes at any one time. A revolutionary solution to the problem was devised by a Belgian orthopaedic surgeon, Professor Joseph Mulier, from the University of Leuven, who approached Thackray’s with his concept of a made-to-measure stem.

Mulier’s idea was for an implant that was manufactured while the patient was still on the operating table, using computer-controlled laser technology. The system had the additional advantage of not needing to be cemented in place, as the Charnley stem did, a factor which caused complications in unexpected revision cases. Together, Mulier and Thackray’s developed a system which they called Identifit. It took about 40 minutes for a titanium stem to be milled and delivered to the operating theatre. The first such stem was inserted in February 1987 with generally favourable results.

Changes in the management structure of the firm were touched on in relation to Charnley, but we should now look in more detail at what took place as the 1960s gave way to the 70s. It was in the prosperous years of the 1960s that the third generation of the family, John and his cousin Paul Thackray, entered the picture. Tod’s son, John, had departed from the tradition of learning the business within the company by undergoing management training, both at Edinburgh University and with a market research company in Amsterdam. Paul, Noel’s son, had intended to work for Thackray’s only temporarily after Army service in a garrison medical centre abroad, but after a stint in the firm doing a range of jobs, his interest in Thackray products grew and he decided to stay on.

When John rejoined Paul in the family firm in the 1960s, all was going exceptionally well for the business. The dramatic increase in demand at home coincided with a surge of new hospitals in the oil-rich countries where Thackray’s had won sizeable contracts. At this time annual exports were about equal to home sales, totalling £1,340,000 in 1971—chiefly due to Charnley products—compared with just under £250,000 in 1960. Success overseas was due in large measure to Export Director Bill Piggin, whose achievement was recognized beyond the firm when he was awarded the OBE for services to Britain’s exports.

Towards the end of the decade, however, alarm bells sounded in the boardroom: the impending abolition of resale price maintenance would hit consumables and result in competitors’ taking over the wholesaling of general sundries, the bulk of Thackray’s business; and there was the threat of losing the US agencies which had been such a profitable source of income since the 1920s, as American companies set up their own operations here.

First, the board recognized the need to update its methods. Computerization was clearly going to be an essential part of streamlining— particularly in stock control, with about 15,000 different items stored at three different warehouses as far apart as Leeds, London and Glasgow (a problem that was resolved with the building of a new warehouse at Beeston in 1974).

Outside consultants were brought in to ease the transition to a computerized system, but most members of staff agree that, to start with, it was a fiasco. ‘If I had ordered what the computer said on day one,’ claimed someone in the purchasing department, ‘Thackray’s would have been bankrupt.’ The extra work over two years in putting right mistakes was considerable for some. Not least for Noel Thackray, who had been closely involved with the whole programme since its introduction. Members of his family feel that that period of stress made him ill and had probably even hastened his death in 1971.

The bottom line of the company’s accounts at this time showed a healthy profit, but both John and Paul Thackray felt that administration was old-fashioned and inefficient. In this respect, however, Thackray’s was no different from any other of the major surgical houses. When John suggested bringing in management consultants, Tod welcomed the idea. It was at this point that Thackray’s had their first contact with Leeds Polytechnic staff, whose role has already been touched on in relation to Charnley.

The appointment of a works manager and massive investment in machinery led to what unquestionably became the most efficient production line of Charnley stems in the world. Meanwhile, manufacture of replacement knees, elbows and external fixation equipment for bone fractures continued alongside, although in smaller quantity than the hip prostheses.

John and Paul Thackray sought further advice from Leeds Polytechnic Department of Management, whose brief was to look at marketing. Their report made it clear that the firm had no concerted approach and that if action were not taken quickly, the healthy position that Thackray’s was in owing to a favourable market environment could soon revert to one of chaos or even decline.

A solution to the general lack of co-ordination within the firm was to restructure the business. The old ‘shop’ system—in which, for example, each department had its own raw materials store even though many of these were common to other departments—was replaced by a new structure, in which the company was divided by function rather than product. To put the scheme into practice, ten new managers were appointed in the early 1970s and, as John Thackray put it, ‘The driving was left to them.’ Delegating management, so that the traditional linear structure was replaced by a pyramidal one, represented a watershed in the company’s organization. It ceased to be a patriarchy, and for the first time a personnel manager was appointed.

The revolution occurring within the company was mirrored elsewhere, with people working shorter hours and trade unions’ influence on industry increasing. The 1970s saw the company’s first strike. This was a remarkable event in a business with no record of industrial action throughout its long history, but less noteworthy when considered in the national context.Throughout the country, millions of workers had been given a cost-of-living increase in the high-inflation days of the mid-1970s. About 300 of the workforce at Beeston walked out in protest at the delay in payment of their threshold award. Union members agreed to return to work after twelve days when they were offered a cost-of-living safeguard.

The otherwise good record of labour/management relations survived this hiccup and the Seventies continued to be a prosperous decade for the company. Widespread hospital building, with concomitant orders for new equipment, was good for business, and increasing profits from the sale of Charnley products were ploughed back into the company.

Towards the end of the decade, John and Paul Thackray took over as Managing Director and Deputy respectively, while Tod remained as Chairman.

A more vigorous approach to marketing led to substantial exports. Hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of equipment was sent to Middle Eastern hospitals and in 1978 the firm won a £2.5 million contract for a royal hospital in Abu Dhabi. This was the first time the firm had scheduled such a project from start to finish. The largest volume of sales was still in surgical sundries for which there was now cut-throat competition. But, as Paul Thackray put it, ‘We were like a corner shop trying to compete with supermarkets.’ If Thackray’s were to remain competitive, they would have to specialize.

Management decided to rationalize their agencies, retaining only exclusive ones or those that complemented their own theatre products. In addition, they began to subcontract some of the more common instruments and simple hospital furniture. This strategy left Thackray’s producing a minority of its own instruments for the first time and it opened the way for manufacturing to be concentrated on new winners, like Charnley, and medium-run items such as plastic surgery instruments. Foreign-made surgical instruments began to show undeniable quality as well as low prices and the company started to import a range of specialist instruments which they marked Thackray Germany.

On the whole, the rationalization strategies worked, but the decision to retain only exclusive agencies could backfire, as Thackray’s found to their cost with an excellent American product, the Shiley Heart Valve. This agency achieved a turnover of £1 million; then, with little warning, it was withdrawn. Profits for the company were halved overnight.

At the end of the successful Seventies, a strong pound hit exports, and cash limits were imposed on the National Health Service. For the first time, profits dropped to break even. In common with the rest of British industry, Thackray’s found themselves having to make staff redundant, dropping from a total of 750 employed to 500 over a period of three or four years—though the number of compulsory redundancies was low. The staff redundancies and the Shiley experience made John and Paul Thackray realize that they would have to take some radical—and sometimes unpopular—decisions, among them the closure of the London office and the firm’s canteen. But they acquired confidence and it was in the 1980s that they undertook what was to be the last major reorganization of the company under family ownership.

They began by splitting the increasingly unprofitable Raymed division (Thackray’s drug department) into two: with Pearce Laboratories on one hand and ostomy and continence products, under the heading Thackraycare, on the other. By manufacturing fewer products and larger volumes, Pearce Laboratories, moved to a factory at Garforth on the outskirts of Leeds, could now outprice its giant competitors.

The new policy, which could conveniently—if clumsily—be called divisionalization, meant a return to division by product area, with each having its own manufacturing, warehouse, sales and marketing, but with the additional advantage of shared centralized services.

In this context, Instruments were now separated from Orthopaedics, which represented the lion’s share of Thackray’s business by 1985, achieving a turnover of £20 million. Expansion at Beeston took place on the proceeds of the sale of Park Street, which Leeds City Council had purchased to make way for additions to the Magistrates’ Court. The Council’s approach to Thackray’s fortunately coincided with the need to find larger premises anyway; and the company’s head office moved to a new leasehold office building in Headingley, on the edge of Leeds.

The remarkable growth of Thackraycare was a success story in its own right. It had its origins in the orthopaedic department of the retail shop in Great George Street. But it was clear to Christin Thackray (who met her husband, John, while working for Charnley product agents in her native Norway) that patients were in need of far more professional help than was available to them. Her idea was for Thackray’s to employ trained nurses to work in the community, fitting the appliances and giving back-up advice. By 1980, Thackraycare took on its first two nurses to put the concept into practice. The old brown-paint-and-cracked-lino image of the orthopaedic department was replaced by an attractive display in the basement of the Instrument Centre which had opened at 47 Great George Street two years previously.

The success of the new appliance centre lay in word-of-mouth recommendation and by 1984, two more were opened, in Surrey and in Bristol. Others, in Oxford, Southampton and Wolverhampton, followed. Most manufacturers’ products were stocked and it was strict policy to recommend a Thackray product only where appropriate. Most patients were referred by healthcare professionals to the centres and the majority were seen in their own homes-an immeasurable improvement for patients.

At the end of the 1980s the family shareholders had to consider how the firm was to continue into the Nineties and beyond. As a predominantly orthopaedic business, accounting for about eighteen percent of the total number of hips implanted internationally, John and Paul Thackray recognized that if the company were to succeed against giant competitors, they would have to develop a global presence. They could foresee potential inheritance tax problems arising for individual shareholders, too.

Given these circumstances, most boards of directors would consider either going public or selling out. The first option was rejected because the family directors felt themselves to be unsuited to the different disciplines the stock market would have imposed. There was every likelihood, too, that Thackray’s would be undervalued compared with American prices. Selling the company did not appeal to John and Paul at that time either; they had not planned to retire for another five or ten years. Although a sale was not envisaged until the mid-1990s or possibly 2000, the company actually changed hands in 1990. What led to this unexpected turn of events?

Orthogenesis was a major investment for the company requiring millions to develop and market it. Thackray’s drew up a list of some of the big names in orthopaedics and, early in 1990, approached them with a view to developing Orthogenesis as a joint venture, or possibly selling that part of the company. But no one was interested: all or nothing was the common response.

In John and Paul Thackray’s view selling the whole company should be considered only if the following criteria could be met: that a high, US-level price was paid; that the buyer should have a similar ethos; that continuity of employment on the firm’s present sites could be assured for the foreseeable future; that the buyer would continue to expand the company.

Among the international companies who showed interest was another family-owned business called Corange. With 90 percent of its business in diagnostic products, pharmaceuticals and biomaterials, but only ten percent of its worldwide sales in orthopaedics (through its subsidiary, DePuy), Corange found what they were looking for in Thackray’s. And Corange could provide the worldwide network and financial resources that Thackray’s needed to assure the company a future as successful in the twenty-first century as they had been throughout the twentieth.

Penny Wainwright

Originally published in “Leeds City Business” by Leeds University Press 1993

Notes

1 Chemist and Druggist, 14 January 1984

2 Kelly’s Directory of Leeds, 1902

3 Thackray Company Prescription Ledgers, West Yorkshire Archive service, Leeds District Archives

4 House Committee Minutes, Leeds General Infirmary Archive

5. S. T. Anning and W. K. J. Walls, A History of the Leeds School of Medicine; One and a Half Centuries 1831-1981, Leeds University Press, 1982.

6. Reality, vol. 1, no. 2, September 1961, Thackray Company Archive, Thackray Medical Museum.

7. Unpublished correspondence, Thackray Company Archive, Thackray Medical Museum.

8. H. McLeave, Mclndoe: Plastic Surgeon, 1961.

9. W. Waugh, The Man and the Hip, 1990.

10 J. Charnley, Manchester Collection (Medical), John Rylands University Library of Manchester.

11 *Registered Trade Mark.

12 *Registered Trade Mark.