The most fundamental issue raised by the Francis Report on Mid-Staffordshire Hospital is not about institutions or even culture but about voice and power: who is heard, who is silenced and who, tragically, dies from deafness. Lack of voice was also at the centre of earlier scandals at Alder Hey, the Bristol Royal Infirmary and Winterbourne View Hospital. It will arise again from the many of the inquiries into other scandals emerging from whistle blowers and patients.

Democracy is the missing dimension in the health debate. When the founder of the NHS Aneurin Bevan said “The sound of a bedpan falling in Tredegar Hospital would resound in the Palace of Westminster” he did not mean Whitehall targets for catching bedpans. He meant that patients would be heard by politicians. We now know that the system is incapable of hearing the people who use and pay for the service, and that thousands have died prematurely as a result.

The Francis Report said “It is a significant part of the Stafford story that patients and relatives felt excluded from effective participation in the patients’ care.” (§1.17, p46) The public had “no effective voice – other than CURE – throughout the worst crisis any district general hospital in the NHS can ever have known.” (§1.23, p47). But just 14 of Francis’s recommendations refer to patient participation on boards or inspections, the accountability of commissioners, role of MPs and organisation of Local HealthWatch. These are useful, but cannot address the profound lack of democratic accountability, involvement and scrutiny in health policy and provision. To address this, patients, carers and the public need a stronger voice at the frontline, where services are provided, and also at the very top, where the design, priorities and funding for health and social care are decided.

Ann Clwyd’s description of her husband’s death “like a battery hen” in Cardiff’s University Hospital and the “hundreds and hundreds” who have written to her show the tragic consequences of not listening. Numerous inquiries such as Alder Hey, the Kennedy inquiry into deaths in Bristol Royal Infirmary and Healthcare for All about people with learning disabilities have produced volumes of recommendations for changes in organization and culture of health services, yet the problems persist because they cannot be answered by institutional measures alone. Tragically the problems won’t be solved by Francis’s 290 recommendations in his 1,782 page £13m report, because the fundamental issues are about power, voice and human relationships that are at the heart of health care.

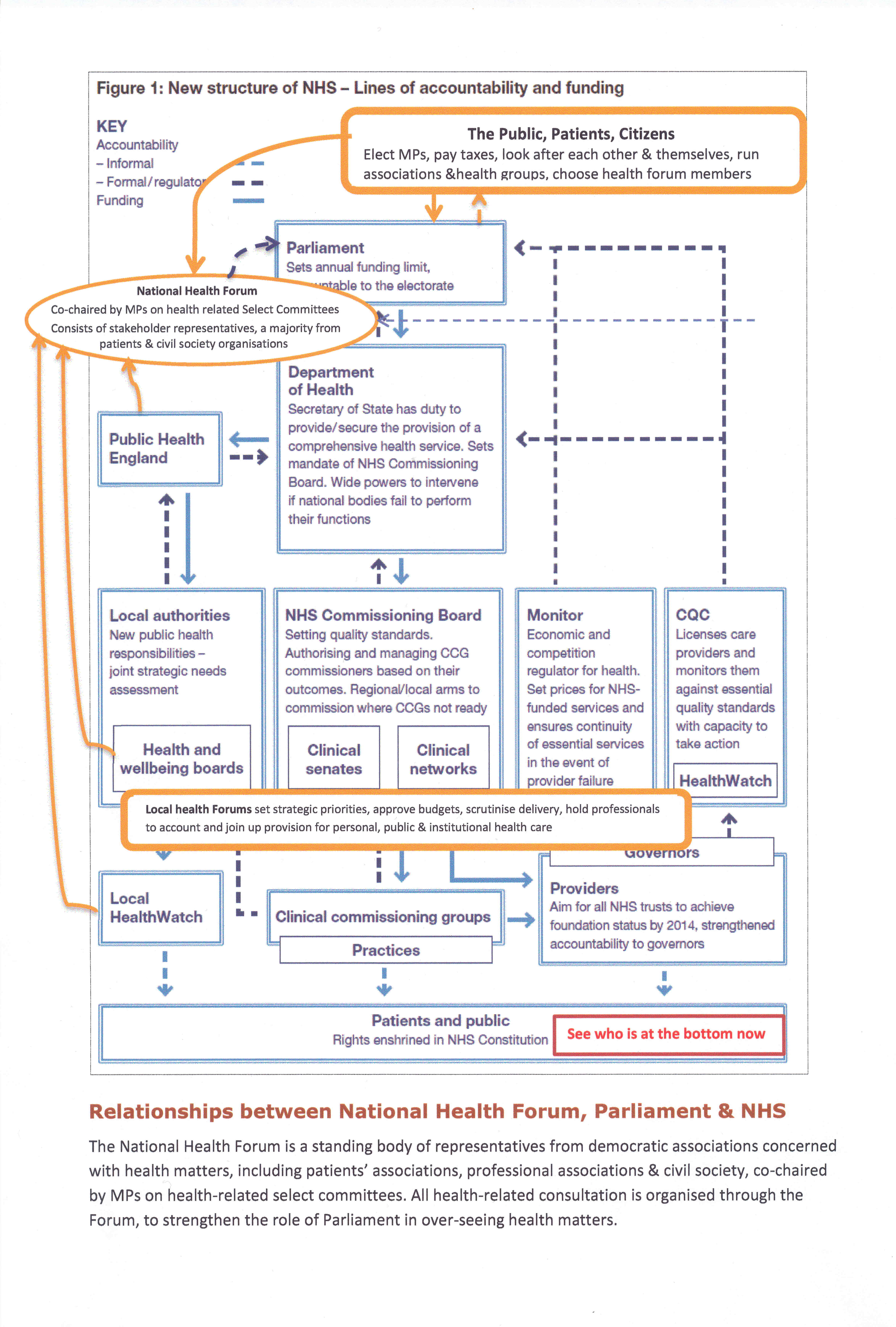

This paper makes the case for a National Health Forum or “Parliament for Health” to give organisations of patients, civil society and other interests in health matters a powerful voice at the highest level, above the bureaucracy of the Department for Health and the NHS Commissioning Board, advising Parliament and the Minister on all health matters. It also calls for local health services to be accountable to an inclusive representative forum linked to local councils and more representative and accountable boards for individual services as part of a wider democratisation of health.

The following section shows why we need a “Parliament for Health” and in part two shows how it would work, followed by a diagram showing how it would fit into existing structures.

Why we need a Parliament for Health

The Francis Report and Ann Clwyd’s experiences are just the latest horror stories about failures in our health and care services. NHS staff are in contact with over 1.5 million patients every day, most of whom get good care and 90% are satisfied, too many people have a bad or even terminal experience through mal-treatment, neglect or hospital acquired infections. More bad news will be revealed as new inquiries are held, whistle-blowers defy gagging orders and more patients’ tell their stories.

Our problems in health are much wider than leadership, management and organisational culture of NHS institutions. Services are just the most visible part of health care. It also includes the way we look after our own health, how we care for each other, where we work or the lack of work as well as the food, drink, tobacco and other drugs we consume and the influence of our peers. Our largest healthcare provider is not the NHS but families, who deal with everyday health of children and the sick as well as long-term care of elderly and disabled people.

These issues present problems which cost more lives and misery than mismanagement at Mid-Staffordshire or any other hospital. Decisions about funding priorities and the allocation of resources are critical for health outcomes in families as well as hospitals. We spend about £1,700 per person per year on health services through taxes, £106bn in 2011. Indirect costs of ill-health are about the same, another £100bn a year or £1,600 each. Add to that the soaring cost of personal care, the lack of support for carers and the value provided by six million unpaid carers (variously valued at £23bn to £119bn, and we have a very complex picture for the state of health in Britain.

If the NHS were a country, its £106bn budget would make it the 55th largest country in the world, about the size of New Zealand or Vietnam in terms of GDP. It would have a seat at the UN (it is represented in the World Health Organisation, WHO) and its civil service, including the NHS Commissioning Board, Monitor and other bodies, would be answerable to citizens through Parliament. Instead, it accountable to appointees answerable to the Secretary of State who alone speaks for us all.

Many urgent issues need to be dealt with in our health services. Some are strategic and others local to an area or institution. But strategic decisions create the framework for the whole system and set the conditions which allow tragedies like Staffordshire and Cardiff University Hospital to occur. The radical changes now sweeping through the NHS combined with rising demand and resource constraints will create many more conflicts over service closures and access to care. These strategic decisions are political, about the priorities, structure and funding for every aspect of health, including the balance between prevention and cure, personal and collective responsibility, or between environmental, societal and medical factors.

Health is one of many areas where our political system has failed for decades and Governments have kept people powerless to do much about it, as whistle blowers in the health service show. Our centrally run health service gives Ministers the illusion of control, so we have had decades of ‘start-stop and start again’ health reorganisations which make it harder for people themselves to take part in creating the provision for health they need.

Successive Governments have grappled with the complexity of preventative health, primary care, hospitals, nursing, the cost and effectiveness of medicines, social care, mental health, an aging population, addiction and myriad issues that affect our well-being. Since 1974 the NHS has been almost continuously reorganised in pursuit of better patient care, greater clinical leadership, devolved responsibility and less bureaucracy. The objectives have been largely consistent, but Governments have taken us on an expensive rollercoaster, plunging and twisting through GP Fundholding, Care in the Community, Family Practitioner Committees, Primary Care Groups, Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) and now Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). While some interest groups (GPs, consultants, dentists) have done well out of this mystery tour, many others have not, the public is losing out, and the cost is enormous. There has been almost no democratic debate the proper framework for health, including the balance between public and private providers, between civic and personal responsibility or the role of employers and business. We have focused too much on publically funded institutions and ignored the bigger role of other factors.

The Francis Report will be added to the shelf of recommendations and another transitory Government will give the NHS another shake. Some improvements may occur, if we’re lucky, but many problems will persist and some will get worse because political attention and resource is elsewhere: when you turn the spotlight on one problem, the rest are left in the dark. Some things may get better due to lack of interference, while others get worse through neglect.

Most battles over health reform are among politicians and the professionals. The public is rarely involved in difficult debates about how to balance priorities between prevention, primary care, social care, hospitals or our £9 billion annual drugs bill (2011), except when mobilised to fight over a particular hospital, treatment or reorganisation.

Whatever the rhetoric, the public has barely a token voice in how we look after health as a society and how services are provided. Formal participation has been channelled through a succession of weak bodies, from Community Health Councils (1974-2003), Patient Forums (2004-8), LINks (Local Health Involvement Networks, 2008-2012) and now Local HealthWatch. There is a tiny amount public participation through representation on health trusts, and more active involvement through fundraising, self-help groups, volunteering and charitable provision such as hospices, but these are largely excluded from decision-making and ignored if they go against the professionals’ wishes. In many areas the voluntary sector, PCTs or local councils have forums for health and social care, which comment on decisions but are powerless.

The 1974 NHS reorganisation created Joint Consultative Committees (JCCs) to promote joint planning between health and local authorities, but they did not have the power to be effective and were abolished. Now the Government is setting up local Health and Well-Being Boards which will face similar challenges and even greater financial pressures than those which undermined the JCCs in 1974 (see Health and wellbeing boards: system leaders or talking shops?).

When the Coalition Government ran into political difficulty over its health service reforms, it set up the NHS Future Forum, a group of health experts led by GP Professor Steve Field, but barely two or three of its 55 members represented patients or the public. It listened to more than 11,000 people face to face at over 300 events as well as engaging with people online, but then public involvement stopped. Then it is set up the Nursing and Care Quality Forum for another burst of consultation.

But Ministers and Parliament do not have the time or capacity to give health matters the sustained scrutiny they need, nor to develop the political framework which balances all the different issues and interests involved in health and well-being. What we need, therefore, is a permanent “Parliament for Health” to grapple with these issues in public. A Parliament for Health could have directly elected representatives (MHPs) or be indirectly elected from local Health and Well-Being Boards and other stakeholder groups, with a majority of from civil society, to ensure that the people are in charge of the professionals, as it should be in a democracy. Part two describes how it could work in more detail.

If all health-related policy and legislation had been systematically scrutinised by “Health Parliament”, with a majority of representatives from patients and the public, feeding into the democratic processes of Parliament, Governments would not have been able to lurch from one reorganisation to another. Sustained public dialogue between interest groups involved in health, including the public, is more likely to have created better patient care, greater clinical leadership, devolved responsibility, less bureaucracy and greater emphasis on public health, health promotion and well-being. Problems like those at Staffordshire, Cardiff’s University Hospital, Alder Hey, the Bristol Royal Infirmary, Great Ormond Street and elsewhere are much more likely to have been raised by “Health MPs”, listened to and dealt with than the regulators who have clearly failed.

An effective Health Forum would be more challenging than the countless consultations, advisory groups and forums run by Whitehall and the NHS, and probably cheaper to run. It could also be a place where issues are discussed frankly and in depth, bringing a wider range of knowledge and experience to bear on policy decisions. It could even make expensive inquiries like Mid Staffordshire, Healthcare for All or the Kennedy inquiry unnecessary, because it would give people a powerful platform above the bureaucracies, linked directly to Parliament.

How would a Parliament for Health work?

A representative National Health Forum within our system of Parliament could bring together representatives of stakeholders concerned with different aspects of health. I suggest that at least half the membership should be representatives of patient groups, democratic organisations of civil society and elected representatives from other tiers of government, including parish and local councillors and MEPs; about a quarter could representatives of staff and professional associations, and the final quarter made up of researchers and other stakeholders. It could be co-chaired by back bench members of parliament from health related select committees. In time it could have directly elected ‘Health Representatives’ as part of to a new kind of second chamber, bringing a wider range of experience and expertise into the political process. But MPs could set up a “Health Parliament” or Forum now, as an extension of the Select Committee to strengthen their oversight of health matters.

A Parliament for Health should have statutory rights to discuss all legislation that impacts on their health, to conduct investigations into the implementation of policy and report directly to the House of Commons through Member of Parliament (the Co-Chairs). It could have the following tasks:

- Propose national priorities in health, for the NHS as well as public health;

- Hold the NHS Commissioning Board, Monitor and other strategic health bodies to account on behalf of Parliament (which should have the final say);

- Scrutinise the work of our representatives on the World Health Organisation, EU Council of Health Ministers, the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) and other international bodies which influence health;

- Promote dialogue round critical issues raised by the Francis Report, the Bristol Royal Infirmary inquiry and other investigations, and scrutinise their implementation;

- Recommend priorities for research and development in health policy and provision;

- Organise public consultation on proposals by the Government, taking consultation on major health matters from the NHS and Whitehall;

- Pre-legislative scrutiny of proposed bills before they are presented to the Commons, to draw attention to health implications

- Scrutinise and revise legislation through a “public reading stage” before the second reading in Parliament;

- Contribute to consensus building, where appropriate;

- Advise and assist on policy implementation;

- Monitor implementation of all policies that affect health;

- Review and evaluate the impact of legislation.

Failures in the NHS are symptoms that Parliament does not have the capacity to exercise democratic oversight and accountability of health services. The Health Select Committee does an excellent job, but it does not have the time to address the vast range of issues and variety of institutions which make up health provision. A Parliament for Health (or National Health Policy Forum) could dramatically increase the knowledge and experience to inform health policy-making. The Forum would be a permanent consultative body, with part-time members, elected for perhaps seven years, longer than a Parliament.

To increase public access and participation, most of its work could be done through a mixture of working groups, open public meetings and online forums. The whole Forum could meet to conclude a “Public Reading Stage” of relevant legislation, to discuss major issues like those raised by Mid-Staff Hospital or contentious policy areas like addiction, inequality in health, obesity, hospital reorganisation, major health bills or other critical issues.

The Government’s proposal of a Chief Health Inspector may be a useful lightning conductor for failings in future, but over a million inspectors go into the NHS every day – patients, their families and frontline staff. They are also the people who will make most difference to the health of the nation, in homes, workplaces, shops and streets as much as in waiting rooms, wards and surgeries. We are the people who determine what happens to our health, we pay for it through our taxes, and we deserve better democratic accountability from bottom to top to make sure that health services and support meet people’s needs with care.

If the Government wants to address the deeper issues in health, it needs to look beyond the institutional matters raised by the Francis Report and give the public, patients, professionals and researchers a forum to scrutinise everything that concerns health and wellbeing to support the Select Committee system and strengthen our Parliamentary democracy and our health.

A National Health Forum will not be enough to strengthen democratic development of health. Local Health and Well-Being Boards need to have greater democratic legitimacy and oversight of all provision for health including hospitals and primary care to look at the actual needs for health and balance of priorities in each area. Access to exercise, parks, playgrounds, fast-food and pharmacies can’t be separated from decisions about GP practices or A&E services. Each hospital, health centre and clinical service also needs a board with independent representatives of patients and the community. By deepening democratic dialogue about health and well-being at all levels we can share responsibility for a healthy society to flourish.

Titus Alexander, Convenor, Democracy Matters, writing in personal capacity

Email: titus@democracymatters.info Tel: 077203 94740

The table shows where a National Health Forum would belong in the current structure of health services.

A ‘Parliament for Health’ is one of 12 Citizen’s Policy Forums proposed to deepen Parliamentary democracy.