It is widely recognised that poverty and ill-health go hand in hand. But despite this, the crucial relationship between income and health is usually misunderstood. Two misconceptions are common. The first, based on the experience of the last few generations, is the assumption that rising prosperity remains the main source of improved standards of health throughout society. As standards of comfort improve so, it is thought, will health. The second misconception is that the only remaining relationship between income and health is the residual relationship between absolute poverty and ill-health. It is assumed that such a relationship will weaken and then disappear as affluence spreads further down the social scale sweeping the last remnants of ‘real’ need before it. Once everyone has attained certain minimum material standards, has a dry house large enough for the family, can afford to heat it, is able to buy adequate food and clothing with a little money in hand for emergencies and extras, that will be the end of any causal relationship between income and health.

A closer look at the evidence shows that both these views are wrong. Economic growth no longer ensures rising standards of health and the elimination of absolute poverty will not neutralise the important influence which income has on health. The health problems of modern societies follow a new pattern which places the social structure under a much more critical light. The picture emerging from recent research is a startling one. Once societies have reached the levels of affluence found in the developed countries further improvements in absolute standards make rather little difference to health. Health differences between developed countries reflect, not differences in wealth, but differences in income distribution, in the degree of income inequality within each society. Among the developed countries this seems to be the single most important determinant of why health in one country is better than in another.

Although income differentials and relative poverty have a profound effect on the scale of health inequalities within each society we are not concerned here simply with health inequalities. Income distribution is one of the key determinants of health standards across society as a whole. This has important policy implications: it suggests that we do not face a choice between maximising overall health status or reducing health inequalities. Quite the reverse. The message is not simply that inequality kills the poorest, but that it reaches well beyond the poor to become the major determinant of health standards among the population as a whole. The evidence leaves little room to doubt that a major programme of income redistribution is now an essential part of an effective policy for public health.

Most of the research mentioned in the following pages is recent and the picture it provides of the relationship between income and health is not well known even to many people working in community medicine and public health. We shall therefore go through the evidence carefully.

International comparisons

In order to distinguish the wood from the trees we shall, before looking at the relationship between health and income among individuals, start by noting some important relationship to be found in the international data.

Among the less developed countries there is still a clear relationship between their average per capita income and measures of health such as average life expectancy. The higher the standard of living in these countries, the healthier they are. Although the relationship is not perfect, it is statistically strong and highly significant.’ However, among the much richer industrial – or post-industrial – countries, improvements in health are no longer strongly related to rates of economic development and increasing per capita incomes.

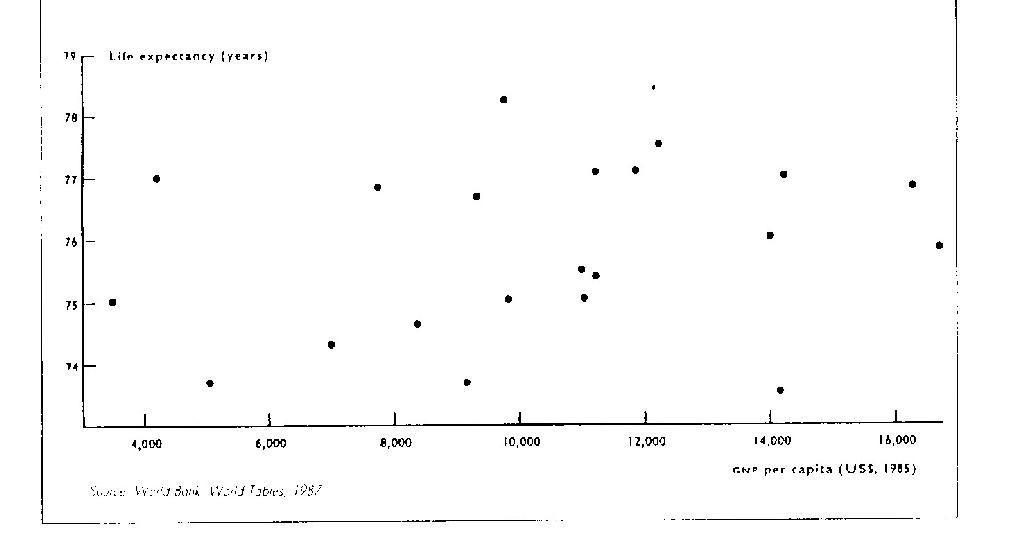

Figure 1: The lack of relationship between GNP per capita and average life expectancy in rich countries. Each point represents a country.

Figure 1 represents a group of rich countries on their own. What happens to the overall relationship across both rich and poor countries is shown below. Figure 2 shows that health is only strongly related to the standard of living among countries below a threshold level of income. Above about $5,000 (1985) per capita the health curve levels out and, as economists would say, further increases in income lead to diminishing health returns.

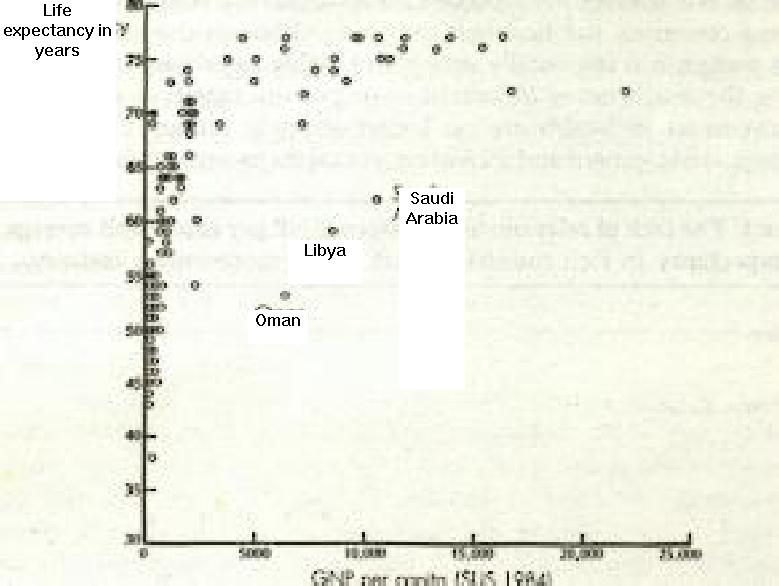

Figure 2: The relationship between GNP per capita and life expectancy in rich and poor countries. (The rich Middle Eastern oil-producing countries with low life expectancy are marked individually) (Reproduced with kind permission from C Marsh, Exploring Data, p213, Polity Press, 1988)

We shall concentrate here on what happens in the richer countries, particularly Britain. Clearly economic growth continues to raise levels of real income in these countries (except in years of recession) and standards of health go on improving. However, the relationship between these two trends is very weak. Not only are growth rates poorly related to the rate of improvement in health, but health in some of the richer countries, like the United States, Luxembourg or (what was) West Germany, is worse than in poorer countries such as Spain and Greece with considerably lower average incomes.

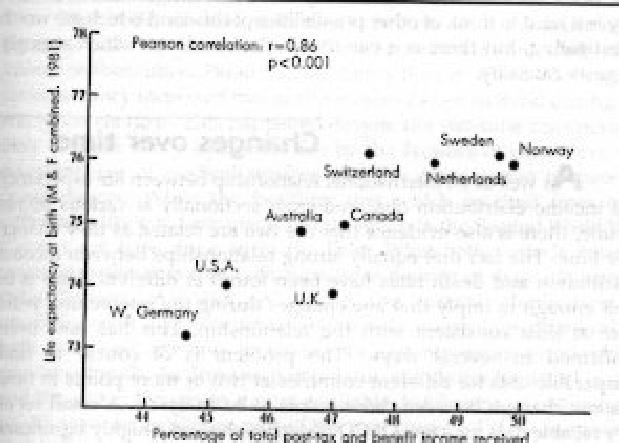

However, among the developed countries there is a striking relationship between the distribution of income and health. As figure 3 shows, there is a clear tendency for people in the countries with the fairest distribution of income to have the longest life expectancy. This relationship exists among both rich and poor countries.’ But as increases in the average level of income or absolute standard of living become less and less important among the richer countries, income distribution becomes more and more important.

Figure 3: The relationship between income distribution and life expectancy

Pearson correlation: r=0.86

Percentage of total post-tax and benefit income received by the least well-off 70 percent of families” Source: Luxembourg income study, working paper 26. World bank World Tables, 1990.

The evidence of the importance of income distribution does not hang on the evidence of figure 3 alone. Indeed, the basic cross-sectional relationship has now been demonstrated four times using different measures of income distribution from different countries at different dates. As well as being robust, it is, statistically speaking, a very strong relationship. Despite the small number of countries for which comparable data was available for figure 3, the correlation is highly significant and suggests that about two-thirds of the variation in life expectancy between these countries is related to differences in their income distributions.

The fact that the relationship between income distribution and life expectancy (or death rates) cannot be dismissed as a statistical artefact does not prove that it is causal. It may, for instance, be thought that it is a reflection of a tendency for more egalitarian societies to have better public services which could benefit health. Differences in the provision of medical services are however unlikely to be the explanation. Modern medical care has surprisingly little influence on mortality in developed countries, and using statistical methods to control for any effect of differences in the level of public and private expenditure on medical care does not alter the relationship with income distributions Not only is it hard to think of other possibilities of this kind which are worth investigating, but there is a variety of other evidence which strongly suggests causality.

Changes over time

As well as an international relationship between life expectancy and income distribution observed cross-sectionally at various points in time, there is also evidence that the two are related as they change over time. The fact that equally strong relationships between income distribution and death rates have been found at different dates is in itself enough to imply that any changes during the intervening years were at least consistent with the relationship. This has now been confirmed in several ways. The problem is of course to find comparable data for different countries at two or more points in time to allow changes between those points to be analysed. A small set of very reliable data for a few OECD countries showed a highly significant relationship between the annual rate of change of life expectancy and the annual rate of change of income distribution over different time periods. As income distribution narrowed, life expectancy increased more rapidly. This time-series correlation was as close as in the cross-sectional data shown in figure 3. Despite using much less comparable data from World Bank sources, a statistically significant but weaker relationship was also found for a larger group of countries.

More intuitively appealing evidence comes from the contrast between the experience of Britain and Japan. At the beginning of the 1970s income distribution and life expectancy were quite similar in the two countries: on both counts they were close to the average of the OECD countries for which data was available. Since then japan has become a very much more egalitarian society. It now has the most egalitarian income distribution in the world and, at the same time, has achieved the longest life expectancy in the world.’ Britain on the other hand has become much less egalitarian. The gap between rich and poor widened dramatically during the 1980s and differences in earnings reached their widest for over a century. Movements in death rates reflect this deterioration: since 1985 British death rates for men and women aged 16-45 years have actually been increasing – even after excluding AIDS deaths.’ Such dramatic examples strongly suggest that changes in income distribution and life expectancy are causally related. Indeed, even the annual rate of change of death rates in Britain seems to be related to the degree of income inequality in the country.

Within Britain the periods which have seen the most rapid increases in life expectancy also stand out as periods of particularly rapid income redistribution. Paradoxically, during the two World Wars civilian life expectancy increased two or three times as fast as it did during the rest of the century.’ This happened despite the war-time disruption of daily life, the worry and stress felt by the families of conscripts, the overstretching of medical services and the deterioration in material circumstances. While the healthier diet which resulted from food rationing is likely to have made a contribution in the Second World War, if could not have done so in the First. What both periods have in common however is that both wars were periods of dramatic income redistribution. As well as seeing the virtual elimination of unemployment and very favourable trends in earnings differentials, both wars saw attempts to ensure at least minimum standards of provision for all. As Titmuss pointed out, the desire for social justice and the attempt to create a more equitable distribution of income and wealth were an important part of the war strategy. “If the co-operation of the masses was thought to be essential (to the prosecution of war), then inequalities had to be reduced and pyramid of social stratification had to be flattened.” The war-time improvements in health were apparently greatest in areas where health had been worst.’

Confirmation that the substantial degree of war-time income redistribution was influential comes from the more accurate data on income distribution available annually for the last few decades. It looks as if even the annual rate of change in death rates in Britain is statistically related to the usually minor upward and downward trends in the degree of income inequality in the country.

It would seem reasonable to suppose that the effect of income redistribution on national standards of health operates by just such a levelling up process. One would expect health differences within the population to diminish as the health of the poorest improved in response to income redistribution.

It is possible to test whether this is happening by seeing if the changes which have taken place in the size of class differences in death rates in Britain reflect trends in the scale of relative poverty. The indications are that they do. Research shows that social class differences in death rates have widened during periods when the proportion of people living in relative poverty has increased, and narrowed when it has deceased.” Before, during and immediately after the Second World War differentials in earnings narrowed and major extensions of social insurance and assistance schemes reduced relative poverty. The result was that class differences in death rates narrowed. By the early 1950s, Britain was a more egalitarian society than it had been before or has been since and its mortality differentials reached the smallest on record. Since then relative poverty has grown, decade by decade, at an accelerating rate. So too has the size of the class differences in death rates. The proportion of the population living in relative poverty (relative to average personal disposable income) has increased from about eight percent in the early 1950s to some thirty percent in the early 1980s. Over the same period the difference in death rates between classes has doubled or trebled.” Instead of simply comparing the death rates of the top and bottom social classes, the change in size of social class differences in death rates is measured across all classes and takes into account the changing class distribution of the population and revisions to the social class classification.

We have seen that there is evidence of a relationship between income distribution and health across countries at a point in time. We have also seen that this relationship holds for changes over time whether you look at changes within a period in a number of countries or at changes over a number of periods within one country. Lastly, we have seen that this relationship seems to work, as one would expect, by narrowing mortality differences within the population. We shall now turn to evidence of a relationship between income and health among smaller groups and individuals within the population.

Population sub-groups

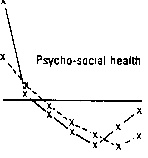

Figure 4: Income and Health: age-standardised health ratios, illness and psycho-social health, in relation to weekly income, demonstrating the effect of £50/week increments in household income, males and females age 40-59 (all of a given age and gender = 100).

50 100 150 200 250 300 Over 350 Midpoint of income range, £/week 1985.

(Reproduced with kind permission from Blaxter, M, Health and Lifestyle, London, Tavistock, 1990, p73)

If more equal incomes increase average life expectancy, this suggests that changes in relative incomes must make a bigger difference to the health of the poor than to that of the rich. Several bits of rather crude cross-sectional evidence on the relationship between the death rates and incomes of different occupations and social classes in Britain have suggested that this might be so.” Though not above criticism, that data suggested that mortality rates rise increasingly rapidly as you move down the income scale.

Much sounder and more recent individual data comes from the Health and Lifestyles Survey and is shown in figure 4. This survey of some 7,000 people was carried out in 1984-85 and used three different measures of health covering disability, physical and psychological health. The shape of the curves are consistent with very substantial improvements in the health of the poor as income is transferred from the rich to the poor. Not only does the shape of these curves imply that the health of the rich may not suffer but, perhaps rather implausibly, suggests they may even benefit from a reduction in their relative wealth.

The most rigorous method of establishing causality is the randomised controlled trial. As yet, no one has set up such a trial to test the effects of income supplementation on health among the relatively poor in the developed world. There was however a randomised controlled trial designed to study the economic effects of negative income tax among a relatively poor population in Gary, Indiana, in the 1970s. Incomes in the experimental group were substantially increased by negative income tax and, although the effects on general health were not assessed, differences in the incidence of low birthweight babies were. It was found that the increase in incomes consequent on negative income tax significantly reduced the incidence of babies born at dangerously low birthweights to high risk mothers. The difficulty of trying to establish causality by purely observational methods is that the rich differ from the poor in too many ways to compare like with like. Whether we take a snapshot at a point in time or follow people as they get richer or poorer, the same problem arises. Even if you control for education and social class, it may be suggested that results reflect more amorphous things such as culture, ‘initiative’ or intelligence. The only way observational methods can avoid selective bias is by studying the effects of changes in income brought about by factors blind to the prior characteristics of the individuals affected.

A study which attempted to avoid these problems looked to see how the mortality rates of whole occupational groups were affected by the changes in occupational earnings differentials during a period which covered both the inflation of the mid 1970s and the industrial upheavals which took place in the few years following 1979. The aim was to see whether occupations which changed their place in the ‘earnings league’ over a ten year period showed corresponding changes in their place in the mortality league. Instead of taking changes simply in the average earnings in each occupation, the study used data on the proportion of people earning different percentages of the average income for all occupations. It also included data on changes in occupational unemployment. The results showed that changes in occupational mortality rates were strongly related to changes in the proportion of people in each occupation earning less than about sixty percent of the national average. Changes in the proportion of people unemployed in each occupation had a similar, independent, effect. The results suggested that people who became unemployed or moved into the low earnings category suffered a thirty or forty percent increase in their risk of death. The fact that changes in the proportion of people in the middle and upper income groups appeared to have no direct impact on mortality rates lends additional support to the role of income redistribution.

State old-age pensions provide another example of income changes which operate independently of the personal characteristics of the people affected. As more than half of all old-age pensioners live on very small incomes it might be expected that their health would be affected by changes in the real value of pensions. A statistical analysis was undertaken to test for a relationship between the annual changes in the real value of pensions and national death rates of old people. Using the death rates of people below pensionable age as controls, it found a close relationship even after allowing for any influence of changes in GNP per capita. The value of state pensions appears to exert a strong influence on the death rates of old people in Britain.

Several studies have of course shown that the unemployed suffer increased illness and raised death rates as a result of their unemployment. Their poorer health cannot be accounted for in terms of an increased tendency for the sick to become unemployed. The excess mortality each year among unemployed men and their wives has been estimated to amount to some 1,500 extra deaths per one million men employed. Whether the health effects of unemployment are a consequence of loss of wages or of related factors such as the loss of self-esteem is not clear, but the similar effects of unemployment and low earnings on occupational death rates (above) suggest that loss of income plays a substantial part.

When looking at relationships such as that between income and health it is often suggested that the causal relationship might be the other way round from that described here. Instead of changes in income distribution affecting health, a tendency for sick people to become poorer would mean that poorer health would widen the income distribution. The possibility of so-called ‘reverse causality’ has been carefully examined in a number of major studies on class and health and on unemployment and health. Although the sick do suffer economically, the direct effects of poverty on sickness seem to be considerably more important. In addition, several of the studies mentioned above – such as the one on the value of state pensions and old people’s death rates, studies of unemployment and health, of changing occupational incomes and occupational mortality rates – were specifically designed to avoid the possibility of reverse causation producing misleading results.

Unlike studies of social class and health, which are based on the economically active population in the working age range (from 20 Years to retirement), the strongest evidence of the importance of income distribution comes from figures of life expectancy for the total population throughout life. Because these are heavily influenced by deaths in childhood and in later life, when people are not earning, there is less scope for reverse causation. Indeed, it is possible to trace a statistically significant relationship between changes in death rates for children (0-19 years old). Lastly, there is fairly clear evidence that income distribution is determined by economic forces, by the trade cycle and by changes in taxes and benefits, rather than by health.

We have now looked at the relationship between income and health cross-sectionally and in time-series, internationally and nationally, within population subgroups and individuals, and the evidence clearly suggests that income distribution is a major determinant of standards of health across society as a whole.