The NHS and Private Practice

18.1 Our terms of reference cover private practice only so far as it affects NHS resources. But the connections between the NHS and private practice are such that, although we have no wish to enter into the “pay beds” dispute, we felt that out contribution might best be made by putting in summary form some of the more important facts about private medicine. We first survey the extent of private practice as far as it is known, then consider the arguments for its benefiting or harming the NHS, and finally we look more closely at pay beds in NHS hospitals.

18.2 Private practice is often discussed in terms of broad principles such as individual freedom of choice and equality of opportunity. We have deliberately tried to avoid such emotive issues by concentrating on the facts. Nevertheless, we have no doubt that this matter will continue to be debated. We hope that in the light of our discussion some of the more extreme attitudes which have been struck in the past might be avoided.

The Extent of Private Practice

18.3 Private practice is an imprecise term. It may include:

- registered private hospitals, nursing homes and clinics, some of which also treat NHS patients on a contractual basis;

- private practice in NHS hospitals, including treatment of private in-patients (in pay beds), out-patients and day-patients; private practice by general medical practitioners, general dental practitioners, and other NHS contractors, including opticians and pharmacists, who provide NHS services but usually also undertake retail or other private work;

- private practice outside the NHS undertaken by medical and dental practitioners, and other staff such as nurses, chiropodists and physiotherapists, who are qualified for employment in the NHS but choose to work wholly or partly outside it;

- treatment undertaken by other practitioners not normally employed in the NHS, such as osteopaths and chiropractors.

Private hospitals and nursing homes

18.4 Private hospitals and nursing homes are required to register with health authorities under the Nursing Homes Act 1975 (in Scotland the Nursing Homes Registration (Scotland) Act 1938 and in Northern Ireland the Nursing Homes and Nursing Agencies Act (Northern Ireland) 1971). The total number of private hospitals and nursing homes registered, and the number of beds they contain, is shown in Table 18.1.

TABLE 18.1

Registered Private Hospitals and Nursing Homes: UK 1977

| Institutions | Beds | |

| England | 1,110 | 30,457 |

| Wales | 45 | 986 |

| Scotland | 84 | 2,847 |

| Northern Ireland | 10 | 256 |

| UK TOTAL: | 1,249 | 34,546 |

Source: health departments.

18.5 There is no formal distinction between private hospitals and nursing Their beds are approved by health authorities for use by four broad categories of patient – medical, surgical, mental health and maternity – but these classifications are not exclusive and some beds are approved for more than one purpose. About 73% of the beds shown in Table 18.1 were for medical patients, 15% for surgical, 11% for mental health, and 2% for maternity.

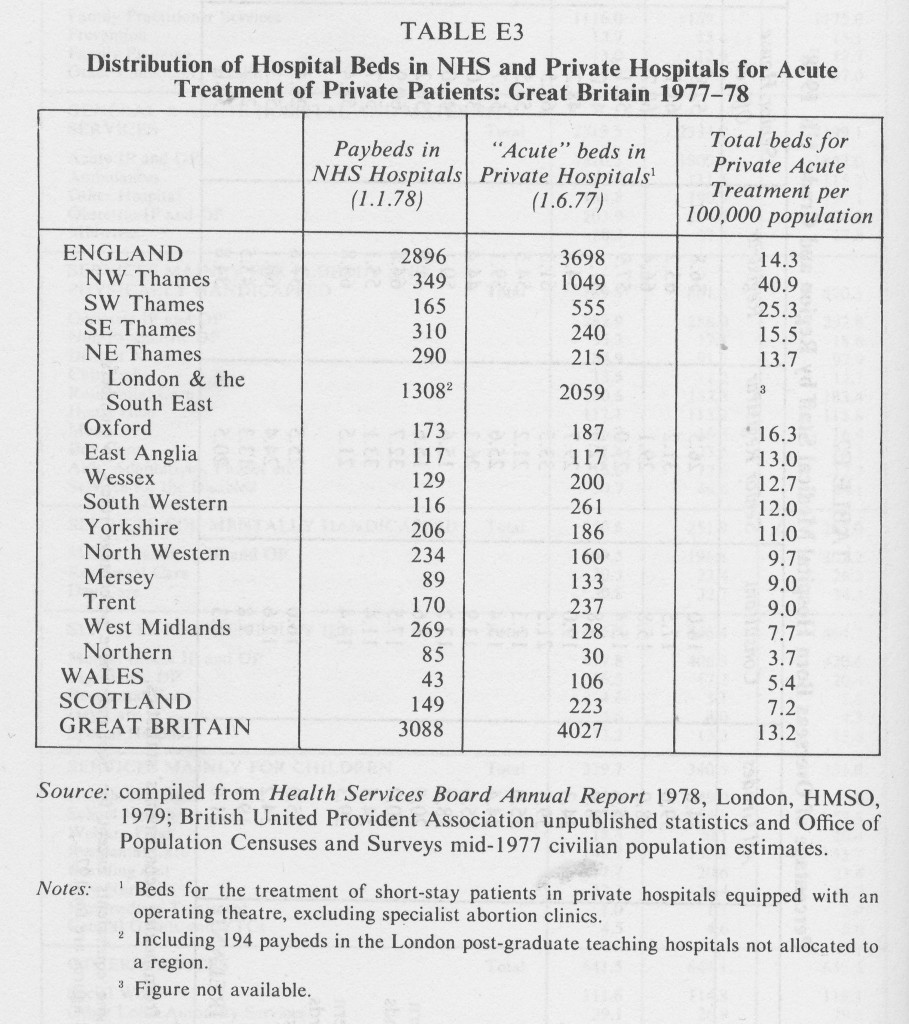

18.6 Of the institutions referred to in Table 18.1, 117 were private hospitals with facilities for surgery, 31 of these being run by religious orders and 44 by other charitable or non-profit making organisations. They concentrate on “cold” surgery. Although no comprehensive figures are available, 88% of the patients treated in the largest group of private hospitals (the Nuffield Nursing Homes Trust) in 1977 received surgical treatment. The distribution of acute beds in private hospitals and nursing homes is shown in Table E3.

18.7 Beds approved for medical patients are used mainly for the convalescence, rehabilitation and care of the chronically sick and elderly. In 1977 there were 116,564 people aged 65 or over in residential accommodation provided by or on behalf of local authorities, compared with 51,800 patients in hospital departments of geriatric medicine. The great majority of these patients are elderly. They receive nursing care and any necessary medical attention is often provided under the NHS by local GPs in the same way as it is for people living in their own homes. Such nursing homes are distributed throughout the country, but there are concentrations in coastal areas, such as Kent, Sussex, Devon and North Wales. There is no doubt that many patients in private nursing homes would otherwise need care in NHS hospitals or local authority accommodation, or would make heavy demands on community services.

18.8 Private hospitals and nursing homes may treat NHS patients on a contractual basis and there are currently about 4,000 beds in the private sector occupied by NHS patients under the care of NHS doctors, about 0.8% of the total beds available to the NHS.

18.9 We visited a number of private hospitals with acute beds, including ones run commercially and by charitable organisations. We found that the disparities between one hospital and another in premises and facilities and in general atmosphere were at least as great as the variations to be found within the NHS. We were not able to judge the quality of medical and nursing care provided, but in some the standard of accommodation was higher than that normally provided by the NHS. Others seemed to offer no advantages over the NHS except a room to oneself, and in some cases not even that. There are of course substantial variations in the cost of private hospitals, but we did not always find that the most expensive hospitals offered the best facilities.

18.10 People turn to the private sector for a number of reasons. One is for the privacy of a single room. Illness is usually distressing and some patients prefer to be alone in their discomfort. Others may wish as far as possible to continue to conduct their day-to-day business and may require privacy and access to a telephone. The convenience of being able to book a date for admission to suit business or personal commitments is obviously important to many people. In our view it should not be necessary to seek private treatment to obtain these advantages (we discussed the availability of NHS amenity beds in Chapter 10). Others may seek private treatment to reduce the time they have to wait for an out-patient appointment or in-patient treatment, particularly where cold surgery is involved. Another reason is to guarantee seeing a particular consultant.

Abortion facilities

18.11 Since the passing of the Abortion Act 1967 (which does not apply in Northern Ireland) most abortions have been performed in private clinics and nursing homes. In 1978 121,754 abortions were performed on women resident in the UK, and 28,015 on non-resident women. Table E4 in Appendix E shows the number of abortions performed in the NHS and in approved nursing homes on resident and non-resident women since 1968. About half the abortions on resident women, and nearly all those on non-resident women, were performed privately. Sixty registered private nursing homes were approved under the Abortion Act, of which 19 were regarded as specialising in abortions.

18.12 Abortion cannot be delayed and if an NHS operation is not readily available a patient must resort to the private sector. There is considerable geographical variation in the proportion of women obtaining an abortion in the NHS, ranging from nearly 90% in the Northern Region to about 22% in the West Midlands Region and 31% in the Mersey Region. This suggests that lack of availability of NHS facilities, rather than real desire for private treatment, is the major factor in most cases where the full cost of treatment has to be met by the patient. Some health authorities have been able to meet most of the local demand but others have not. Equality of access to health services was one of the objectives we set out in Chapter 2 and abortion is a conspicuous example of lack of such equality.

18.13 We doubt whether the NHS could meet the demand for abortion in the immediate future without reducing other services, and this will not normally be justified. Nevertheless, there are ways in which health authorities could increase the number of abortions provided. There is evidence that many abortions can be safely carried out on a day-care basis, with considerable savings in resources compared with in-patient treatment; and it may also be possible in some areas for abortions to be undertaken, with suitable supervision, by outside agencies on behalf of the NHS. We recommend as a broad objective that health authorities in Great Britain should aim to increase to about 75% of all abortions on resident women the proportion performed within the NHS over the next few years. The additional cost might eventually be about £2.5m per annum (less if day-care abortions were widely introduced).

Private practice in NHS hospitals

18.14 Consultants who undertake private practice may, if facilities are available, admit their private patients to designated private beds (pay beds) in NHS hospitals or as day patients, or see them as out-patients. Not all NHS hospitals have pay beds and the number of pay beds and the proportion of consultants undertaking private practice has been falling for many years. Table 18.2 gives figures.

TABLE 18.2

Number of Pay Beds and Proportion of NHS Consultants with Part Time Contracts: UK 1965 and 1976

| 1965 | 1976 | |

| Number of pay beds | 6,239 | 4,859 |

| Part-time consultants as a percentage of all NHS consultants | 56.9% | 42.8% |

Source; compiled from health departments’ statistics.

Note: ‘ Excluding Northern Ireland.

18.15 Under half of all NHS consultants work part-time. While there may be a few who work part-time for other reasons, the great majority do so because they want to undertake private practice. However, the opportunities for private practice vary according to specialty and locality and this is reflected in the proportion of consultants with whole-time contracts shown in Table E5 in Appendix E. In England and Wales in 1978 only about 15% of consultants in the major surgical specialties had whole-time contracts, while about 90% of those in pathology, geriatrics and mental handicap worked whole-time in the NHS. Over 69% of consultants in the Northern region had whole-time contracts, compared with under 40% of those in the Thames regions.

18.16 Up-to-date information on consultants’ earnings from private practice is not available, but figures for 1971/72 published by the Doctors and Dentists’ Review Body showed that part-time consultants on average derived about one third of their income from private practice. In current terms, this would represent about £6,000 per annum.

18.17 We referred in Chapter 14 to the proposed new consultant contract. It is impossible to predict with confidence its effect on consultants’ private practice, though it is intended to offer more encouragement than present However, this will not be the only influence, and the volume of private practice will probably depend as much on the adequacy of NHS services, the demand for private treatment and the availability of facilities as it will on the consultants’ form of contract.

18.18 A certain amount of non-NHS work, mainly for public authorities may be undertaken by consultants who hold whole-time NHS contracts and are not eligible to undertake private practice as defined in their terms and conditions of service. This includes examinations and reports for industrial injuries or court purposes. For most consultants, earnings from this source are probably very small.

General medical and dental practitioners

18.19 General medical and dental practitioners are free to accept as much private work as they wish, subject to it not interfering with their NHS obligations. Probably almost all general medical practitioners undertake work, such as examinations and certificates for insurance or employment purposes, for which they charge a fee. For the majority, income from this and from private treatment of patients will represent a very small part of their total earnings. In 1971/72 about two per cent of general practitioners’ income was derived from hospital, local authority and non-NHS public sector work, and about six per cent from private practice.

18.20 Private practice by general dental practitioners is more substantial. In 1977 some 11% of their time was spent on work other than in the general dental service, probably mainly on private practice. The evidence we have received has expressed concern at the tendency for general dental practitioners to restrict their NHS practices to concentrate on private practice or provide only some forms of treatment on the NHS.

Patients

18.21 About 50% of private patients treated in NHS pay beds or receiving acute treatment in private hospitals are covered by provident associations. Altogether there were some 1.12 million subscribers to provident schemes in 1978, of whom 869,000 were members of group schemes. Subscriptions often cover more than one person and in 1978 a total of 2.39m people were covered. The total number of subscribers rose in 1978 after remaining fairly steady in recent years, but within the total, group subscriptions have tended to increase and individual subscriptions to fall. As might be expected, such evidence as there is suggests that most individual subscriptions are taken out by older members of the community and people with relatively high incomes. The proportion of private patients from overseas is not known, but except in some of the larger private hospitals in London is probably small.

Size of the private sector

18.22 The overall scale of private practice in relation to the NHS is small. In England about two per cent of all acute hospital beds and six per cent of all hospital beds are in private hospitals and nursing homes. The proportions in the rest of the United Kingdom are lower. In 1976 about four per cent of “acute” patients, and about seven per cent of surgical patients, were treated in private hospitals. However, about 50% of abortions on women normally resident in the UK were performed in the private sector, and private nursing homes make a significant contribution to the long-term care of the elderly.

18.23 A recent estimate put expenditure on private health care in the UK in 1976 at £134 million. This figure excluded most expenditure on abortions and on long-term care in nursing homes (neither of which is normally covered by private health insurance), and on private general medical and dental care. Information from the Family Expenditure Survey for 1976 suggested that total expenditure on private health care was of the order of £200 million. This compares with the total NHS expenditure in 1976 of £6,249 million, and on this basis the private sector accounted for about three percent of total expenditure on health care in the UK in that year.

Private Practice and the NHS

18.24 The difference in scale of the private and public health care sectors suggests that private practice could have at most a marginal and local effect on the NHS. Nonetheless, it was put to us that the private sector subsidises the NHS in some ways, and that the NHS subsidises the private sector in others. We consider these arguments briefly below.

18.25 A point frequently made by supporters of private practice is that patients who opt for private treatment in effect pay twice for their health care: they contribute to the NHS through taxation and NHS National Insurance contributions, but they also pay for the private care that they receive. Much the same argument is made in relation to private education.

18.26 Second, most consultants who undertake private practice are on “maximum part-time” contracts. Under such a contract a consultant may undertake private practice but is required to devote “substantially the whole of his time” to NHS work. He is paid nine-elevenths of the full-time salary. Some consultants argue that this arrangement constitutes a subsidy for the NHS since the consultant is paid only a proportion of the full-time rate but is required to carry the same case load as a full-time consultant. The situation is further complicated because the present consultant contract is open-ended and there are no stipulated hours of duty. In a survey undertaken by the Doctors’ and Dentists’ Review Body in 1977 whole-time consultants reported averaging 7 hours per week and maximum part-time consultants 43.2 hours per week on NHS work. There is room for argument both about the interpretation of the survey and the nature of the consultant contract, but the 51/2 hours difference is less than the two-elevenths difference in salary. If the proposed new consultant contract were to be introduced this particular grievance would disappear.

18.27 Third, we were told that private practice contributed towards the funds available for medical research. Academic staff holding honorary NHS contracts may not normally benefit personally from any private practice they The arrangement is that such fees are paid over to the university department and used for research purposes. The amounts involved are likely to be a small proportion of the total funds available for medical research, although they may be significant for some medical schools.

18.28 Others argued to us that the taxpayer subsidises the private sector by financing staff training and the provision of radiology and pathology It was also said that skilled manpower was attracted away from the NHS. The argument about training is that the private sector does not have to incur the expense of training its own doctors, nurses, and other staff but relies on those trained in the NHS. Few private hospitals are approved by the General Nursing Council for nurse training, and post-graduate medical training takes place exclusively in the NHS. Pathology and radiology carried out in the NHS for private patients is normally paid for, but the availability of such facilities may relieve the private sector of providing what might in some places be an uneconomic service.

18.29 There is no doubt that the NHS has from time to time suffered from shortages of particular groups of staff both locally and nationally. However, bearing in mind the modest size of the private sector it is difficult to believe that such shortages were often due to NHS workers leaving for the private sector. A number of the private hospitals we visited employed a high proportion of married women. They argued that the NHS was unable to provide sufficient opportunity for part-time employment. We did not find this argument wholly convincing – in 1977, 38% of hospital nursing and midwifery staff in the UK were employed part-time – but the private sector may be able to offer more flexible working hours and better conditions of service for some staff. Hard information on the effect of the private sector on NHS staffing is difficult to come by. Our view is that the impact of private health facilities on NHS staffing will depend mainly on the local employment position and could only be determined by detailed local enquiries. We have no information that would enable us to assess the effect nationally of the private sector on NHS staffing but it cannot be large.

18.30 Some less specific points were put to us. It was suggested that the existence of a private sector provides a yardstick against which the performance of the NHS can be measured and shows where the NHS is failing to meet consumer demand. We accept that demands on the private sector may well show where the NHS is deficient, but we think that there is ample scope within the NHS for comparing standards of performance and identifying strengths and weaknesses. A related point made was that the strict financial discipline imposed on the private sector enables resources to be used more efficiently than in the NHS. This kind of point is virtually impossible to test.

18.31 Most of the considerations referred to above are unquantifiable. There is no doubt that the private sector contributes to the health care of the nation, albeit on a small scale. In two particular areas, provisions for the elderly and abortions, the contribution is significant. It would be virtually impossible to establish how far health workers are diverted from employment in the NHS. We have reached no conclusions about the overall balance of advantage or disadvantage to the NHS of the existence of a private sector, therefore, but it is clear that whichever way it lies it is small as matters now

Pay Beds and the Health Services Board

18.32 Under the NHS Acts, health ministers may designate beds in NHS hospitals for use by private patients. The patients are required to pay the full cost of accommodation and services provided by the hospital. Fees for medical treatment are paid directly to the consultant concerned. Pay beds have always constituted a small proportion of total NHS beds, and their number was declining before the Health Services Board started work in 1976. Tables 18.3 and 18.4 show this trend.

TABLE 18.3

Pay Beds in NHS Hospitals: UK 1956-1979

Number of pay beds

| 1956 | 1965 | 1970 | 1976 | 1979 | |

| England | 5,723 | 5,534 | 4,353 | 4,150 | 2,666 |

| Wales | 106 | 91 | 68 | 60 | 39 |

| Scotland | 929 | 614 | 328 | 234 | 114 |

| Northern Ireland | 430 | n/a | 376 | 415 | 149 |

| UNITED KINGDOM | 7,188 | 6,239 | 5,125 | 4,859 | 2,968 |

Sources: compiled from statistics provided by the health departments’ and the Health Services Board.

18.33 The number of patients treated in pay beds has also declined from a peak in 1972, as Table 18.5 shows. Average daily occupancy by private patients of paybeds in the UK was 1,762 (45.6%) in 1977.

TABLE 18.4

Pay Beds as a percentage of total beds in NHS hospitals: Great Britain 1965 – 1976

| 7965 | 7970 | 1976 | |

| England | 1.25 | 1.02 | 1.07 |

| Wales | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.25 |

| Scotland | 1.00 | 0.52 | 0.39 |

Source: compiled from health departments’ statistics

TABLE 18.5 Patients Treated in Pay Beds: England and Wales 1950 – 1977

| 1950 | 1966 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 |

| 78,274 | 101,696 | 114,856 | 120,274 | 116,272 | 113,221 | 97,641 | 94,323 | 93,877 |

Source: Lee, Michael, Private and National Health Services, London, Policy Studies Institute, 1978.

18.34 The Health Services Act 1976 established an independent Health Services Board to be responsible for the progressive withdrawal from NHS hospitals of authorised accommodation for the treatment of private patients, and for the regulation of the development of private hospitals and nursing The Board’s powers of regulation apply only to hospitals and nursing homes which have, or would have, more than 100 beds in Greater London or 75 elsewhere. Smaller developments have to be notified to the Health Services Board but are not regulated. The Act also provided for the revocation within 6 months of Royal Assent of 1,000 pay bed authorisations and the submission of recommendations by the Board for the introduction of common waiting lists for private and other patients in NHS hospitals. Although the Act does not extend to Northern Ireland, the government of the day indicated its intention to pursue a similar policy on private medical practice there when the Act was passed.

18.35 The first 1,000 revocations of pay bed authorisations required by the Act were made in 1977, and the Health Services Board has since made four further sets of proposals for revocations. At 1 January 1979 there were 2,819 pay beds in Great Britain, compared with 4,444 in 1976. The initial revocations were based on the non-use or under-use of authorised pay beds for which average daily occupancy was taken as evidence, but the Board has now begun to take into account also the availability of suitable alternative accommodation and whether “reasonable steps” have been taken to provide private sector alternatives.

18.36 The strongest argument put to us in favour of the retention of pay beds was that as far as possible a consultant should be able to undertake private practice while remaining “geographically full-time”, in other words that he should be able to treat both his private and NHS patients in the same place. “In this way the waste of time and effort involved in travelling to and from private consulting rooms and clinics elsewhere, and the need to maintain a separate office staff and to arrange for independent laboratory investigations can be avoided.” The presence of pay beds in NHS hospitals makes it more likely that consultants will be on hand to attend to their NHS patients, and has the additional advantage that the full facilities of the NHS are available to private patients in an emergency.

18.37 One argument against pay beds is that the charges made do not meet the full cost of treating private patients, and that the NHS is therefore subsidising private practice. Charges for private patients are determined by health ministers on the basis of the average costs incurred in the appropriate class of hospital. They are intended to include a reasonable contribution towards capital expenditure but do not take account of variations in facilities provided in individual hospitals. In general, the charges appear to cover the revenue costs of treating private patients in NHS hospitals, but we are not convinced that they cover the capital element adequately. The calculation of the capital element is based on average capital expenditure on all hospital beds in recent years, expressed as a cost per occupied bed per week. This bears little relationship to the full capital cost of providing a hospital bed in the private sector. The Employment and Social Services Sub-committee of the Expenditure Committee of the House of Commons pointed out in 1971 that the weekly charge to meet the full capital cost of a hospital bed would be very much higher. A new private hospital, unless supported by charitable funds, would need to cover in its charges both the interest and depreciation costs of its capital, and we recommend that the NHS should determine the capital element of pay bed charges in the same way.

18.38 We were told that the existence of private practice within the NHS facilitates and encourages abuse. It was suggested that hospital staff, including junior doctors, nurses and domestic staff, were expected to provide services for private patients outside their normal range of duties without additional pay, and that payment was not always made when hospital equipment and facilities were used for private work. The most frequent and serious allegations, however, concerned the speedier admission of private patients, either to pay beds or after a private consultation to NHS beds. We have no firm evidence that such abuses are extensive, and we consider that it should be possible to deal with them administratively. Nevertheless, we regard it as important not only that the NHS should be fair to all its patients, but also that it should make every effort to be seen to be fair, and we deplore such “queue jumping”. Agreement has now been reached between the health departments (Northern Ireland excepted) and the medical profession on the introduction of common waiting lists for urgent and seriously ill NHS and private patients. We welcome this and hope that these arrangements can soon be extended to all hospital patients.

18.39 There has been speculation that the phasing out of pay beds will lead to an increase in the number of private hospitals. The Health Services Board recognise that there is likely to be a “significant expansion of the private sector from late 1979 onwards”. This will probably provide more facilities for surgery. We see no objection to such expansion, which at least initially may amount to little more than the replacement of the pay beds removed from the NHS, providing that the interests of the NHS are adequately safeguarded. This is one of the responsibilities of the Health Services Board. However, although the Board has powers to control larger developments (over 100 beds in London and 75 elsewhere) they cannot regulate developments below these limits; nor, more importantly, can the Board consider how the aggregate of several such developments within a locality may affect the NHS. We think that if the interests of the NHS are to be adequately safeguarded the Board should have the power to consider the aggregate of several developments within a locality, perhaps on the basis that authorisation should be required for any proposal which increases the total number of private beds within a locality above a specified level. We recommend that the powers of the Health Services Board should be extended in this way.

18.40 Pay beds arouse strong emotions. Many doctors regard them as an essential element of their professional independence as well as a source of additional income. Other health service workers, including some junior doctors, resent both the additional work they claim is imposed by private patients and what they see as the purchase of privilege by a small minority within a public service. When the controversy is raging, patients suffer. We do not consider the presence or absence of pay beds in NHS hospitals to be significant at present from the point of view of the efficient functioning of the NHS.

Conclusions and Recommendations

18.41 We are concerned with private practice only insofar as it affects the NHS. We have concentrated on the facts so far as they are known. Information is lacking that would enable us to reach precise conclusions about the relationship between the NHS and private practice, but it is clear that the private sector is too small to make a significant impact on the NHS, except locally and temporarily. On the other hand, the private sector probably responds much more directly to patients’ demands for services than the NHS, and provides a useful pointer to areas where the NHS is defective. One such is clearly the provision of abortion services: half the abortions performed on residents of the UK are undertaken privately. Another is in the provision of nursing homes for the elderly; and patients waiting for cold surgery in the NHS may opt to pay rather than suffer discomfort and inconvenience for months or even years. Other important reasons for choosing the private sector are the convenience of being able to time your entry to hospital to suit yourself, being assured of reasonable privacy and choosing your own doctor. The NHS should make more effort to meet reasonable requirements of this kind.

18.42 From the point of view of the NHS the main importance of pay beds lies in the passions aroused and the consequential dislocation of work which then occurs. The establishment of the Health Services Board led to a welcome respite from discussion of this emotional subject. However, for the Board to carry out its function of safeguarding the interests of the NHS, it seems to us that it should be able to control the aggregate of private beds in a locality: this appears to be a loophole at present.

18.43 We recommend that:

- health authorities in Great Britain should have the broad objective of providing for about 75% of all abortions on resident women to be performed in the NHS over the next few years (paragraph 18.13);

- the capital element of pay bed charges should cover both the interest and depreciation costs of the capital investment in pay beds (paragraph 18.37);

- the Health Services Board should be given power to control, and a responsibility to consider, the aggregate of beds in private hospitals and nursing homes when any new private development is considered in a locality (paragraph 18.39).