SHA’s Maternal, Newborn and Child Health working group responds to the 2024 Labour manifesto.

An in-depth report on maternity services, also called “In Place of Trauma”, will be published later this year.

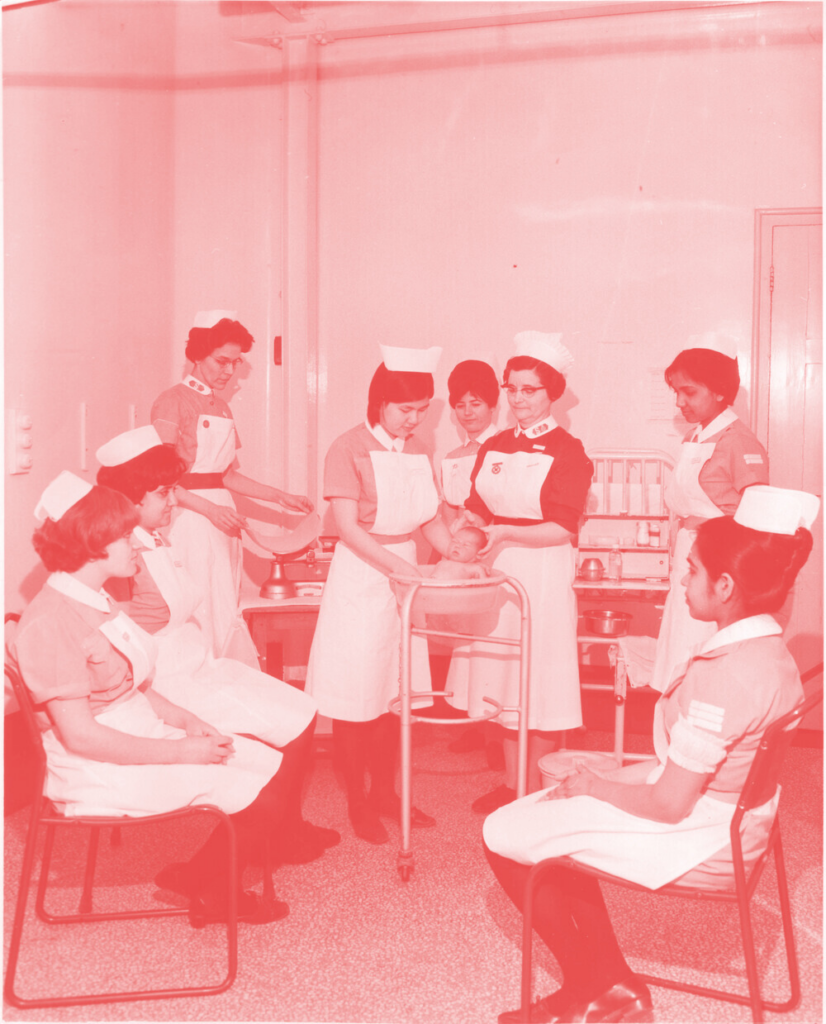

photo source: https://eastendwomensmuseum.org/blog/call-the-midwife-a-century-of-salvation-army-district-midwifery

In ‘Build an NHS Fit for the Future’, the Labour Party’s 2024 manifesto pledges to focus on a number of preventative strategies to improve the nation’s health. Considered in relation to maternity services, the pledges align with the strategy set out in the 2016 National Maternity Review (NHS England, 2016). At the heart of the review, is a plan to deliver safe and personalised care via community hubs. Midwifery continuity of care models (where every pregnant woman receives care according to her needs from a known midwife throughout pregnancy, birth, and the postnatal period) would work in partnership with GP’s, obstetricians, medical specialists and other health and social care professionals to deliver high-quality care. This is likely to result in women reporting more positive experiences of pregnancy and birth, with less Caesarean sections, instrumental deliveries or episiotomies (Sandall et al, 2024).

Research indicates that 4-5% of women develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) post-birth. In the United Kingdom, as many as one in three women report aspects of their birth experience as traumatic. The failure by maternity healthcare professionals to deliver safe, personalised, and compassionate care directly contributes to women’s experiences of trauma. These are the findings of the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Birth Trauma, published in May 2024. In order to tackle the issue of birth trauma, the group has called for a National Maternity Improvement Strategy (APPG, 2024).

The backdrop to the report, the current landscape in maternity services, is stark.

- 67% of maternity services have been rated as ‘inadequate’ or ‘requires improvement’ by the Care Quality Commission (Parliament, House of Lords, 2024).

- Maternal mortality in the United Kingdom has risen to rates not seen for over twenty years, with women from black ethnic backgrounds almost three times more likely to die during birth or postnatally, and Asian women almost twice as likely to die, than white women. The apparent decrease in black maternal mortality risk is largely due to the rising background maternal mortality rate among white women, rather than any specific improvements for black communities – the next Labour government will need to bear this in mind when implementing its promise to “set an explicit target to close the Black and Asian maternal mortality gap”. Maternal mortality rates for women from the most socioeconomically deprived areas are twice those for women from the least deprived areas. (NPEU, 2024). The situation is also concerning for marginalised and “exceptionally vulnerable women” such as refugees, LGBTQ+ women, prisoners and those who have been through the care system, trafficked or experienced domestic violence or sexual abuse – all of whom are more likely to experience poorer maternity care and resultant trauma (APPG, 2024).

- Progress to reduce rates of stillbirth is stagnating (Sands and Tommy’s Policy Unit, 2024)

- Despite recruitment and retention strategies, chronic shortages of midwives, obstetricians and anaesthetists regularly result in unsafe staffing levels in maternity units. A blame-focused response to repeated maternity scandals fails to address the underlying problems of an understaffed, deskilled and demoralised workforce. Will Labour’s manifesto pledge to “ensure that trusts failing on maternity care are robustly supported into rapid improvement” break this cycle by targeting root causes?

- Prolonged deskilling of the midwifery workforce due to loss of experienced midwives, compounded by the fact that those who remain are unable to adequately train, supervise and mentor juniors due to an ever-increasing workload. Labour’s pledge to train thousands more midwives must be matched with a credible strategy for retention, in order to deliver the quality care that women need.

- Hospital and unit closures, reducing choice and safety for women and their babies.

- Increasing complexity of cases, in line with advancements in fertility treatments and medical care for chronic conditions.

- Rising public health problems such as obesity, diabetes and alcohol and drug misuse.

The incoming Labour Government must prioritise the APPG’s recommendation for a National Maternity Improvement Strategy, and a Maternity Commissioner (reporting directly to the Prime Minister). Both should be implemented with immediate effect. The strategy should focus on the following key areas:

- Giving power to maternity service users. Their diverse voices should be at the heart of strategies to improve care. If we TRULY listen to women, we are more likely to deliver services that meet their needs.

- Deliver local ‘Neighbourhood Health’ maternity services via integrated community-based, women’s health hubs. In line with the Women’s Health Strategy (Department of Health and Social Care, 2022), the focus should be on women’s health and care needs across the life course (including maternity) and should move away from a disease-orientated approach.

- Focus on preventative health. ‘Sure Start’ type programmes to target inequalities, help eradicate the black and Asian maternal health gap and to address the specific issues faced by “exceptionally vulnerable women” (as defined in the May 2024 APPG Birth Trauma Report). Undergraduate and postgraduate training curriculums to be designed to meet the needs of all marginalised and vulnerable women.

- Prioritise maternal mental health in line with physical health. Improve recruitment and retention of specialist perinatal mental health professionals.

- Introduce midwifery continuity of care for all women in the United Kingdom. Improve recruitment and retention to deliver this model and expand the midwifery workforce. Begin by addressing the current staffing and skills crisis (The UK is currently 2500 midwives short).

- Work with all relevant Royal Colleges and healthcare unions to target pay and working conditions to improve recruitment and retention of staff and expand workforce capacity.

This needs to be realised in conjunction with an across-the-board resurrection of a chronically depleted national health service, so that women and girls have access to high quality primary health care as well as specialist and emergency care when they need it, for themselves and for their families. At the heart of this, a proper understanding and realisation of the role of the midwife is needed. As described in the Lancet Midwifery Series, universal care is delivered by midwives to all women and their newborns, with ‘additional care’, e.g. medical, obstetric, neonatal, mental health and social services, available to those who need it. This requires effective interdisciplinary collaboration.

To achieve this, we need to staff the women and not the wards. This is the essence of continuity of care models – in other words, there needs to be a wholesale move of services out of hospital and into the community, with midwives as lead professionals for straightforward cases and as co-ordinators of care for complex cases. The midwives ‘follow’ the women into hospital, midwifery-led units or homebirths, as appropriate.

Birth trauma results from failures in care and should not be seen as an inevitable consequence of pregnancy and birth. It is possible to improve women’s experiences of maternity care and health outcomes by implementing midwifery continuity of care models, delivered via integrated ‘Neighbourhood Health’ hubs. Services should be focused on preventative health, reducing inequalities, and meeting the needs of women across the lifespan.

Authored by:

Jo Gould RM, Dip HE, BA(Hons), PGCE, MA, PhD Researcher in Maternal Health, City University, London.

Patricia Schan, Retired midwife and clinical advisor and member of SHA’s Central Council

Dr Rathi Guhadasan MBBS MRCPCH DTM&H MSc SHA Vice Chair and London branch secretary.

References

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Birth Trauma (2024). Listen to Mums: Ending the Postcode Lottery on Perinatal Care. Available at: https://www.theo-clarke.org.uk/sites/www.theo-clarke.org.uk/files/2024-05/Birth%20Trauma%20Inquiry%20Report%20for%20Publication_May13_2024.pdf (Accessed 24th June 2024).

Department of Health and Social Care (2022). Women’s Health Strategy for England. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/womens-health-strategy-for-england/womens-health-strategy-for-england#access-to-services (Accessed 24th June 2024).

National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (2024). Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risks through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK. Available at: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/data-brief/maternal-mortality-2020-2022 (Accessed 24th June 2024).

NHS England (2016). The National Maternity Review: Better Births. Improving outcomes of maternity services in England. A Five Year Forward view for maternity care. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf (Accessed 24th June 2024).

Parliament. House of Lords. (2024). Performance of Maternity Services in England. Available at: https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/performance-of-maternity-services-in-england/#fn-4 (accessed: 20th June 2024).

Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF et al (2014). Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. The Lancet 384 (9948):1129-45.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)60789-3/fulltext (Accessed 20th June 2024).

Sandall J, Fernandez Turienzo C, Devane D, Soltani H, Gillespie P, Gates S, Jones LV, Shennan AH, Rayment-Jones H (2024). Are midwife continuity of care models versus other models of care for childbearing women better for women and their babies? Available at: https://www.cochrane.org/CD004667/PREG_are-midwife-continuity-care-models-versus-other-models-care-childbearing-women-better-women-and (Accessed 25th June 2024).

Sands and Tommy’s Policy Unit (2024). Saving Babies’ Lives 2024: Progress Report Summary. Available at: https://www.sands.org.uk/sites/default/files/Saving_Babies_Lives_Progress%20Report_2024_Summary.pdf (Accessed 25th June 2024).