Proposals before parliament to sell the state owned Plasma Resources UK (PRUK) are under attack by MPs as described on page 1 of the BMJ on 23/3/13. This has naturally caused concern as in the UK blood has been donated freely and products derived from it have been processed by the transfusion services as part of our NHS and supplied to the clinicians at cost price.

There has been some confusion that donations from the UK could be sold which is not the case, but what is at stake is loss of control of production with concerns for safety and affordability.

Because of a small but incalculable risk that vCJD could be transmitted by plasma the UK transfusion service established PRUK which purchases plasma from abroad and privatisation will mean losing control of supply of important treatments to market pressures. It also appears to be another gift from the UK taxpayer to the market as £540 million has been spent to establish the company being offered for sale at a suggested £200 million.

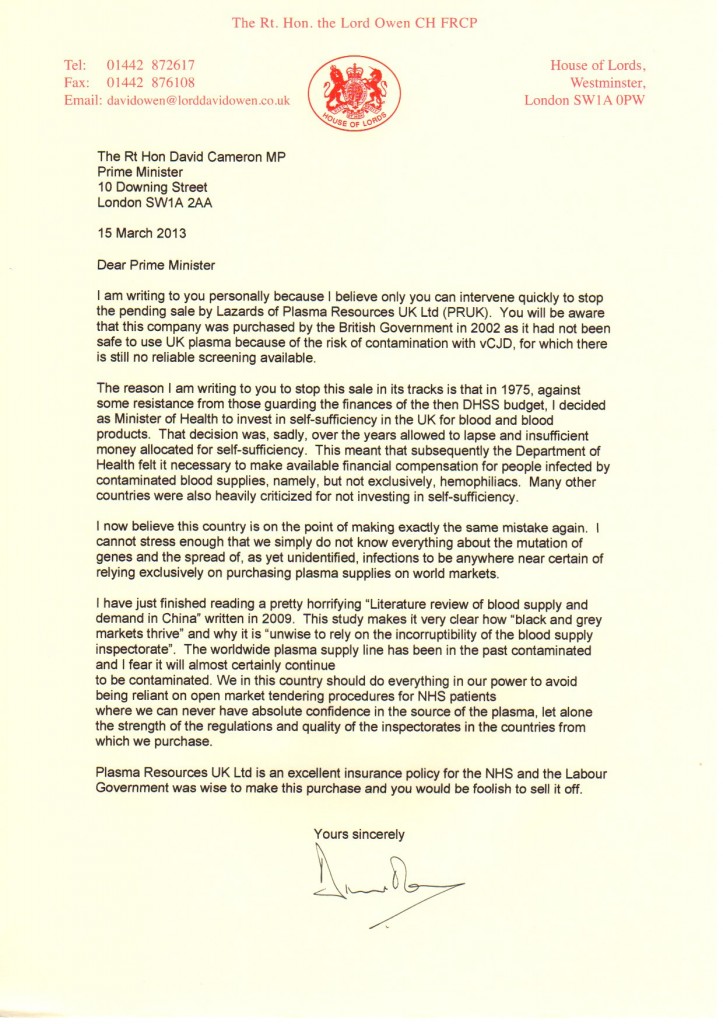

Lord Owen has written to David Cameron to express his concern about safety standards given the risk that the current stringent standards may not be maintained and he is awaiting a reply.

In the UK blood has been given as an act of altruism for those who need it an arrangement that transcends finance and was described elegantly in ‘The Gift relationship’ by Titmus (Oakley, A. and Ashton, J. (eds.), The Gift Relationship: From Human Blood to Social Policy by Richard M. Titmuss (original edition with new chapters) London: London School of Economics and Political Sciences, 1997, paperback, £14.99, viii+ 360pp (ISBN: 0753012014)).

Summarised here by Prof Teijlingen of Bournemouth University in the journal Sociology

“When The Gift Relationship was first published in 1970 it raised much discussion and was generally well received. It influenced social policy, for example, the US National Blood Policy in the mid 1970s. This book is still the only comparative study of the organisation of national blood supply in Britain and the USA (with references to other countries). In this new edition outdated material, including the original preface and appendices, has been removed. The editors aimed ‘to preserve the original power and arguments of Titmuss’s text in such a way that they can be read as relevant to the situation today’ (p.4), whilst five chapters have been added: a new introduction by Ann Oakley and John Ashton, AIDS and the gift relationship in the UK by Virginia Berridge, Transfusion medicine towards the millennium by Vanessa Martlew, A mother’s gift: the milk of human kindness by Gillian Weaver and A. Susan Williams and an Afterword by Julian Le Grand.

Titmuss made the link between the way blood was supplied and the quality of that blood. In the United States, where blood is treated as a commodity, money is to be made by individuals selling their blood. This will attract people who have an incentive to lie about their health status. Titmuss (pp.129-130) quoted Del Prete who argued that those who sell their blood ‘who might need money to buy food and other necessities of life is a person who cannot be trusted.’ In Britain, voluntary donors do not have the same financial incentive to lie about their health, therefore the quality of blood collected by blood transfusions centres is much safer. This argument seems to be widely accepted at the time …..but on occasions there have been urgent calls from the transfusion services for additional blood donors in certain parts of England to come forward to avoid a shortage in blood stocks.

Berridge provides another example indicating that it is not simply voluntary donations that make blood safer, but the way the blood donation is organised. Although the English and Scottish blood transfusion services both rely on voluntary donations: ‘The Scottish service was centrally organised and achieved self-sufficiency in the early 1980s; this, it was later argued, was a prime reason why the spread of HIV among haemophiliacs in Scotland was so limited’ (p.21). Berridge suggests that the idea that ‘the value of altruism in ensuring a safe blood supply was both vitiated and shown to be more complex’ (p.15) in the HIV era. Moreover, Berridge (p.16) noted that although blood donation in Britain and elsewhere in Europe is voluntary, this volunteer image ‘fronted systems which had become highly dependent on commercial sources. Plasma brokers operated with blood as their commodity like any other’ as part of the international trade in blood products. “

Self sufficiency in blood transfusion has been taken for granted red cells and whole blood is a national resource but plasma is treated differently and products made from plasma are treated as pharmaceutical products. Some of these e.g. factor VIII for the treatment of haemophilia can be synthesised by recombinant technology which will reduce the need for plasma but the need still outstrips the supply and UK plasma is unlikely to be considered safe for processing whilst the risk from vCJD exists. This will be for years to come as there is no reliable test for the infection that could be brought in on the required scale.

Concerns about safety arise when paid donors are used as viral screening cannot be 100% effective because of mutations and newly emerging infections, the window period between acquiring an infection and registering a positive result, and because lapses in manufacturing standards may not always be detected allowing potentially dangerous products to reach the market. Recently a batch of Octagam – a commonly used immunoglobulin was withdrawn following reports of thromboembolism which may have resulted from problems in manufacture.

Lord Owen refers to a “pretty horrifying Literature Review of blood supply and demand in China” describing how “black and grey markets thrive” and why it is “unwise to rely on the incorruptibility of the blood supply inspectorate”

Historical background in the UK

Pre 1990 – An agreement was reached between the Government, MRC and the Lister Institute and the Blood Products Laboratory was established with funding from the Ministry of Health. Enlarged facilities for plasma fractionation and freeze-drying were established.

In 1991 it was renamed the Bio Products Laboratory to reflect the internal market in the National Health Service and in 1993 it became part of the National Blood Authority. In 1998 the BPL began purchasing its plasma from the States due to concerns over vCJD in the UK and in 2002 the DoH formed DCI Biologicals Inc to purchase US company Life Resources Inc to supply all of the BPL’s plasma. BPL became an operating division within new Special Health Authority, NHS Blood and Transplant, in 2005. On 31 December 2010 the BPL was vested into a limited company, Bio Products Laboratory Ltd, and ownership transferred to the Department of Health, with BPL Ltd and DCI Biologicals Inc brought under the same DoH holding company, Plasma Resources UK Ltd.

So NHS Blood and Transplant has no say in its sale meaning that the price and availability will be dictated by market forces.

Plasma Resources UK Ltd now looks set to leave the NHS and the consequences could be

- Loss of control of supply of plasma products in UK

- Possible reduced supply if the new company has no obligation to supply according to the clinical need

- Increased price to make the venture profitable for the new company

At present they produce coagulation factors, immune sera and intravenous immunoglobulin which is being used in increasing amounts as an immnunomodulating agent i.e. is used to interfere with the immune response in conditions which are thought to have an autoimmune component – which includes many poorly understood illnesses. There are reports of Intravenous immunoglobulin use in conditions as diverse as toxic megacolon and dementia with little good evidence of cause and effect.

It is also used to help improve immunodeficiency where there are reduced natural immunoglobulins which includes congenital conditions naturally occurring illness and increasing numbers of patients receiving chemotherapy.

NICE guidance supports its use in only two conditions, neonatal jaundice and immune thrombocytopaenic purpura and the Department of Health’s response to the increased demand and limited supply is a guidance document of recommendation based on strength of evidence

This is one of the more overt cases of rationing of a scarce product and an opportunity for our NHS to increase production so that we could become self sufficient, an opportunity that may well be missed.

As in many areas where disease mechanisms are poorly understood or few effective treatments are available there will be enthusiasts for trying treatments with little evidence such as Intravenous immunoglobulin which could drive up costs, reduce the supply to treat patients where there is real evidence of benefit, or through competition on price alone, expose patients to unnecessary risk.

In the past the transfusion service has been publicly owned and has responded responsibly to clinical need, within the limits of its resources. We now will be entering a new environment where market forces will determine supply. The experience so far is that companies will seek the best returns on their investments and that production of more plasma products in commercial terms is not attractive.

The early day motion presented to the House of Commons stated “the UK will be left buying its plasma supplies on the open market where there are supply chain issues of the sort that saw horses being relabeled as beef”.

As with other changes of supplier the devil may be in the detail and you may not know what you’ve got until you lose it – our transfusion service has always put safety first, reacting promptly to every identifiable risk and continuing production.

If the sale goes ahead we need reassurance that these exacting safety standards will be maintained, that the current supply levels will be maintained and that the companies will not form a cartel to make excessive profits from a limited resource.